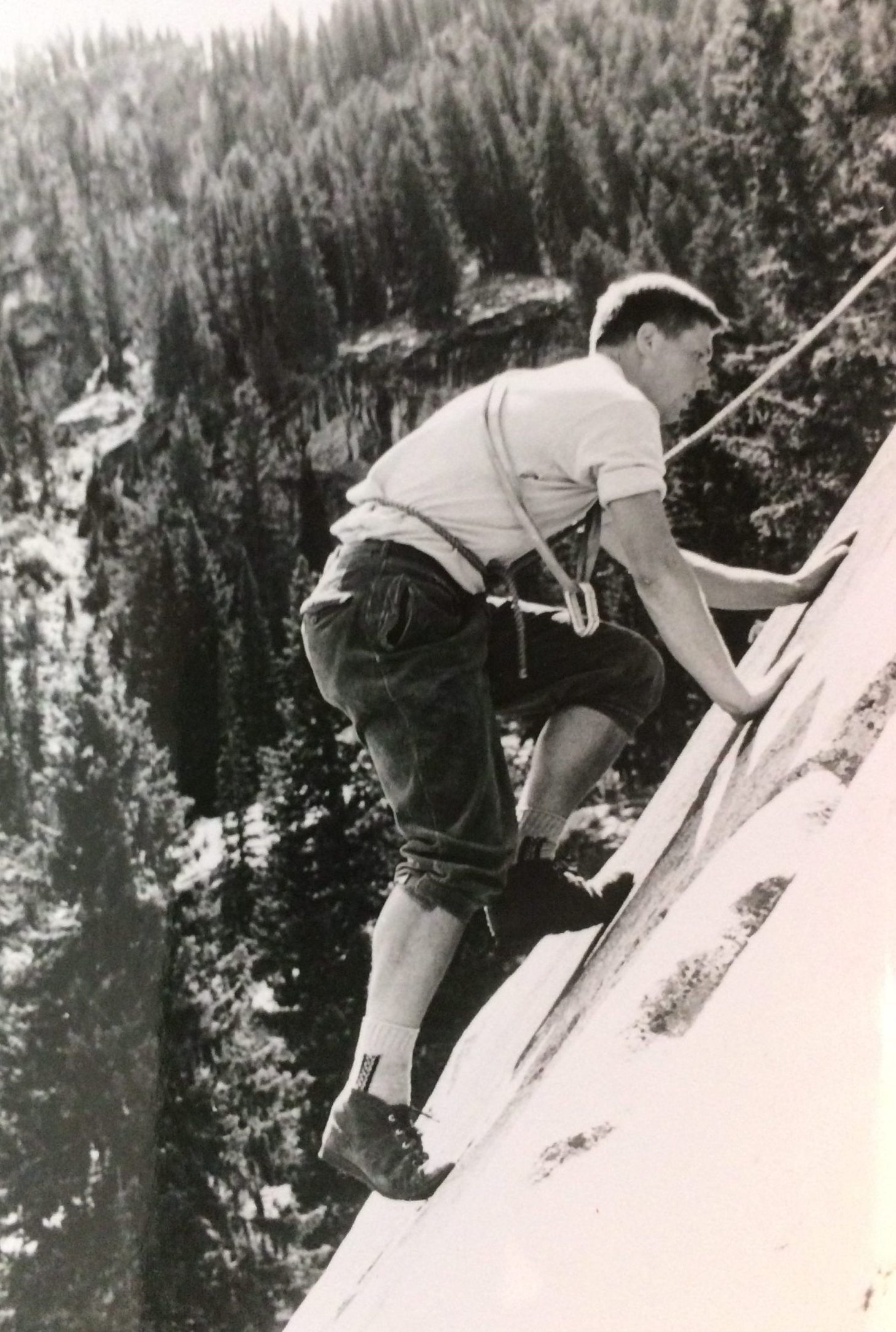

A Profile of Peter Lev, Exum Guide and owner from the early 1960s to the mid-2000s

To read Part 1: From Benchwarmer to Mountain Guide, click here.

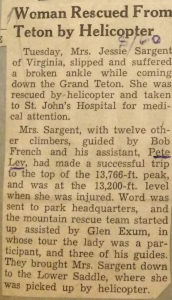

Guiding wasn’t all fun and games, though. On August 9, 1960, Peter assisted Bob French on a climb of the Grand Teton – likely his first trip as an assistant guide. The group had summited successfully and were on their way down when one of the clients slipped and fell. Bob was below and managed to stop her from plummeting to her death. She had dropped 15 feet and couldn’t put weight on her leg. When they removed her boot, it was clear she had severely broken her ankle, as her foot was turned in the wrong direction. Bob took the rest of the party to the non-technical terrain below the Saddle and then ran down to get help, leaving Peter to stay with the injured woman.

They stayed there all day and all night. Peter ensured she was comfortable in the pile of jackets and spare clothing the other clients had left, as they were worried she might get hypothermic sitting in the shade on the mountain’s west side. He and Bob had decided it was best to not do anything to her ankle and not to move her. In any case, there was nowhere to move her to. She had landed on a small ledge, with her feet pointing towards Idaho and her head resting between two rocks. Peter tied her in and secured her to the wall with a rope under her shoulders, and then they passed the time guessing when the sun might reach them. It didn’t arrive until just after noon.

Other climbers passed by and offered encouragement. One, an Englishman, was a doctor and confirmed that her ankle was indeed broken and provided her with codeine to help manage the pain. His climbing partner left her his red woolen hat. Around 5pm, Sterling Neale, another guide, reached them with two sleeping bags, ropes, clothing, and food. They got her into one of the bags, retied her securely to the wall, and then set up fixed ropes to assist the rescuers that would hopefully arrive the next morning.

They spent a cold night on the ledge, joined after dark by Al Read, who had been sent up to help with the rescue. Sterling left them about 2am, heading back down to the Saddle to get his party ready for their climb of the Grand. He’d been walking up to the hut with four clients when Bob French had passed him on the trail and apprised him of the situation.

When morning came, so did the rescue team, which included Glenn, Jim Langford (the district ranger), Pete Sinclair (newly appointed to the Jenny Lake Ranger station), Mike Ermath, George Kelly, and Dave Dornan (who would later become an Exum guide). Dornan was the first ranger to reach the scene, and he found the patient to be quite stoic despite her pain. The team placed the injured client into a litter and began the slow, torturous process of lowering her down the mountain. One man would belay from the top, wrapping the rope around a solid rock to provide friction. Six more rescuers, three on each side, distributed the weight of the litter amongst them via canvas straps around their shoulders and carefully picked their way down.

At times they had to drag the litter across the rocks. Once, they all slipped on the scree and fell, but the belayer kept them from disaster. Those in the rear had to be careful not to kick rocks down onto those in the front. It was exhausting work after an already exhausting and cold night, but they finally succeeded in getting her down to the Saddle.

The helicopter was waiting, and the plan was to lash the litter outside the aircraft. Realizing this and trying to allay any fears, Peter told her, “This will be fun!” But she disagreed and begged to be allowed to ride inside the bird. The rangers relented as long as she didn’t mind having her foot down, and she was just fine with that. Many years later, she wrote a book about her life, including a chapter on this rescue.[1] She was hugely inspired by the risks the guides and the rangers took to get her, this woman they hardly knew, down to safety.

Peter was equally impressed by her. He says clients were tougher in those days – and this woman was tough! Her name was Jessie Sargent, and her husband would later become the governor of Massachusetts. To this day, the spot she fell is known as Sargent’s Chimney.

Grateful for a Motorcycle Helmet

In 1961, Peter’s first full summer at Exum, he was teaching a basic school and setting up the overhanging rappel. They rigged belays on the rappels differently in those days and had stiff, braided ropes. He was using a knot the guides had recently learned, a double sheath knot for tying two ropes of different sizes together.

In those days, no one – clients or guides – wore helmets. But the client Peter picked to go down the rappel first had ridden out on a motorcycle and happened to be wearing his helmet. Peter doesn’t know why he chose him to go first, but he did.

Peter was standing near the cliff’s edge to belay, as was the guides’ practice. Just as the client went over the lip, the knot came undone. Peter had a split second in which he saw the rope flashing by and realized that if he tried to stop the client’s fall, he’d just get pulled over himself, so he suppressed the instinct to grab the rope. The client cracked his helmet in two and broke his leg pretty badly, but it could have been much worse if he hadn’t been wearing his motorcycle helmet. And had Peter gone over the edge with him, Peter almost certainly would have been killed or seriously injured.

Peter is confident he tied the knot correctly and thinks that when he was getting the ropes set up, the stiff, cable-like end of the knot snagged on the bark of the tree it was tied around and got pushed through. Nevertheless, he had no doubt he’d be fired and was reluctant to return to the office. The Tetons were his whole life at that time. The thought of losing all he’d found there made him incredibly sad.

With a heavy heart, he went to talk to Glenn. To his surprise, Glenn told him to take the class back out the next day and finish it. So he did. This was back when people were unlikely to sue. The client was hurt, but he wasn’t mad. He even came back a year or two later and climbed again. Peter was incredibly relieved that Glenn had given him this second chance. It seemed that Glenn had confidence in him and saw potential that Peter himself couldn’t yet see. His career at Exum was not meant to end so soon.

Guiding the Exum Way

Glenn was an “old-fashioned American” who thought the European way of dragging clients up the mountain wasn’t appropriate for Americans. The Exum way of guiding reflected the self-reliance in the country that had grown since the end of World War II.

Peter soaked up this philosophy, believing it was important for clients to be capable and self-reliant – able to belay others, tie themselves into the rope, etc. For many years, the school had belay test rigs on one of the steep cliffs at the practice rocks. Clients learned to hold a leader fall by belaying a truck tire dropped from higher and higher heights.

Peter recalls that clients were grittier back in the 60s. They might not have had the gear, but they had the spirit and eagerly took on climbing challenges. And quite a challenge it was for folks from sea level who might never have seen mountains like the Tetons before. Sometimes it was so hard he couldn’t understand why they would want to climb. He never heard a client say it was easier than they thought it would be – it was always the opposite.

But he thinks, in general, people found climbing to be an uplifting and satisfying experience and were typically elated at having scaled the Grand or whatever it is they had set out to do. He felt he was doing good work, much more suited for him and his beliefs than bomb building or other things which might have escalated the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union that marked much of his career.

Guiding people into the mountains was a positive thing, he believes. It helped people get away from their day-to-day lives, take a break, get out into nature, push themselves, and go back better able to do the things they needed to do. It also put him in a position to be helping others who had run into trouble out in the mountains.

Struggling with a Madman

In July of 1962, on the way down to the hut after climbing the Grand with clients, he heard calls of “Help!” coming from the Middle Teton. Peter eventually spotted something high up on the glacier and went to investigate, leaving his clients in a safe spot. He found two climbers: one injured, one deceased. They had been climbing a steep snow gully when one of them slipped. Their ice axe belay didn’t hold, and they had fallen at least 1,000 feet before their rope got snagged in a crevasse, arresting their fall. It was too late for one, but Peter got the injured climber, Buford Brauninger[2], down to level ground with the help of two other climbers in the area. Peter continued down with his clients to alert the rangers, leaving the other climbers with the injured man, who would be flown out by helicopter the following day.

That wasn’t nearly as dramatic as the rescue he and many of the guides found themselves involved in a few weeks later. It started off with a relatively small, unrelated incident. He’d just gotten back down from another trip up the Grand – unsuccessful due to the snow – when he heard there was a rescue underway. A friend had broken her leg, and he and two other guides spent most of the night helping the rangers get her off the mountain.

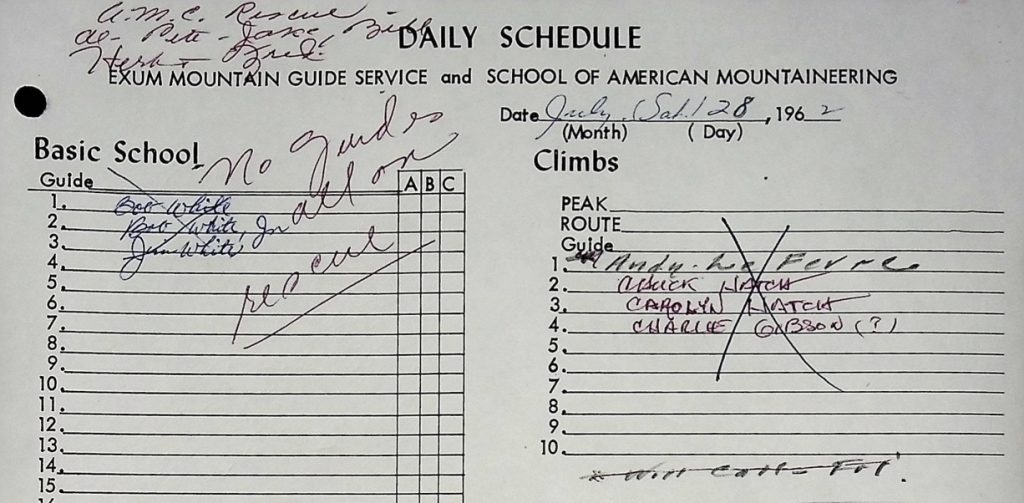

No sooner had that rescue been accomplished when word came that 10 climbers were overdue on Grand Teton. The rangers wanted the help of all of the guides, and they got it. The school canceled all classes and climbs so the guides could assist with the massive rescue operation.

Rangers Pete Sinclair, Peter’s friend Jim Grieg, and Rick Horn had gone ahead to find the lost climbers. Those climbers were on a trip organized by the Appalachian Mountain Club. The club had failed to sign out with the rangers before departing, so at first, the rangers didn’t even know they were overdue. Afterward, in a letter home, Peter said, “This group was totally incompetent and would not have been signed out in the first place. Most were inexperienced & had entrusted their lives to a leader they did not know & who turned out to be some sort of a nut. He took them up into one of the more difficult & most dangerous areas of the mt. Before we reached them they had spent 2 days & 2 nights (without proper clothing & completely wet) out. It had been snowing for one of those days. We expected to find 10 dead people.”

To their surprise, they didn’t. Nine of the ten were still alive, huddled under three rain ponchos on a tiny ledge in a steep couloir, although barely so. They were all in various states of hypothermia, hardly even able to acknowledge the presence of the first rescuers on the scene. Sinclair, Grieg, and Horn started slowly lowering the nearly frozen climbers. Peter and his fellow guides found them near dark and took over the lowering from the exhausted rangers, who had climbed hard for five hours just to reach the group.

“The lowering was rough – over jagged rocks, overhangs, and through waterfalls. The people could do little to help themselves – most could not move their arms & legs.” The descent off the rock wall went well, but they still had over 1,000 feet of 45-degree ice on Teepe’s Glacier to cover. The plan was to tie all the ropes together and lower everyone at once. By now, it was icy cold at 1 o’clock in the morning, and many survivors were showing signs of “losing their minds.”

Exum guides Herb Swedlund and Jake Breitenbach had gone down about 300 feet to chop out a platform in the ice where they could receive the climbers as they were lowered. Peter was standing on another small platform he’d chopped out about halfway between the top of the glacier and Herb and Jake. The first group had already passed by him when he heard Jake yell out that someone had untied from the rope – they’d just had an empty loop pass them. At that moment, Peter realized someone was climbing up towards him in the dark. The man didn’t have a headlamp (only the guides and rescuers did), nor did he have an ice axe or crampons, and Peter was concerned he’d fall, so he hurried down to get him tied back in.

“With very wide eyes he said that he wanted to die, he was going to heaven & that I was the devil and keeping him from it. Then he grabbed my ice axe (which I was attached to by a wrist sling) & my arm. I thought he would pull us both off. I could not quite believe it at first. I yelled for a rope from the fellows above. I tried to tie it on & just at this moment – he & I were struggling very hard, I standing on only the front points of my crampons and he on much less – Rick Horn came down and grabbed him from behind. He let go of me and I got as far away from him as I could.”

Rick was able to get the man tied back into the rope, and then he also got away from him as quickly as he could, climbing back up to the rest of the group waiting above. But the man followed and attacked again. His name was John Fenniman, and in his delirium, the rescuers and their headlamps were “one-eyed devils” trying to lower him into hell, and he had to kill them all to get to heaven.[3]

Fenniman was long past the point of reason, and as he continued to charge the rescuers, all in precarious positions on the icy slope of the glacier, Rick Horn kicked him in the head and knocked him out. At this point, Peter wrote, “This mania was starting to spread. Various victims would announce that they could not take it any longer & were going to do something drastic.” Somehow, Rick, Peter and the guides and rangers lowered all nine people down to solid ground. Rick made a particularly heroic effort. Every time Fenniman regained consciousness, he would begin to fiercely struggle and fight, so Rick had to continue knocking him out for everyone’s safety. Many of the victims suffered horrible frostbite, but all survived. Nothing short of a miracle, considering the conditions and the unexpected fight with a deranged man.

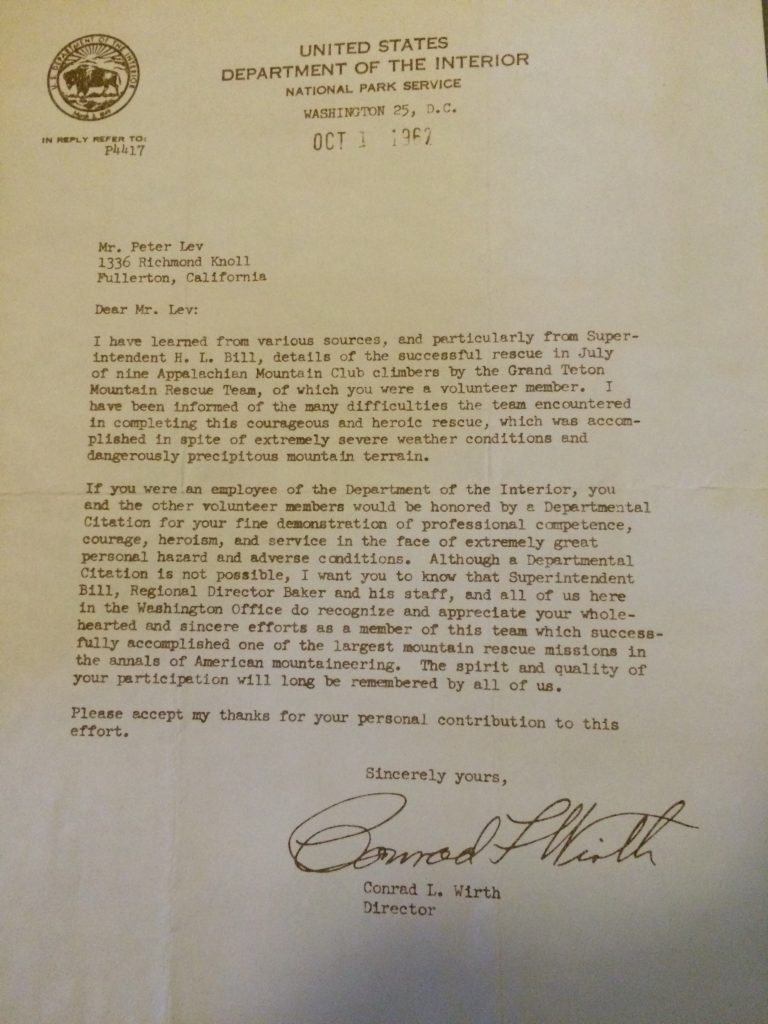

Peter wrote to his family, “The Park wrote us all letters thanking us & I am told we will be paid for our time – about $60, roughly what we would make on a Grand trip.” He later received a letter from the Department of the Interior, which read: “I have been informed of the many difficulties the team encountered in completing this courageous and heroic rescue, which was accomplished in spite of extremely severe weather conditions and dangerously precipitous mountain terrain. … All of us here in the Washington office do recognize and appreciate your wholehearted and sincere efforts as a member of this team which successfully accomplished one of the largest mountain rescue missions in the annals of American mountaineering. The spirit and quality of your participation will long be remembered by all of us.”

Unforgettable Clients

Peter had many memorable clients over the years, but not always for the best reasons. Once, a client in an Intermediate School class Peter was teaching suddenly started screaming that he would jump. He tried to untie himself from the rope, but Peter and the others in the class secured his hands and double-tied his knots to keep him from throwing himself off the cliff. With the assistance of another guide, they managed to lower him to the ground and get him some help. It turned out the client had come to Exum wanting to die in a noticeable, public way. Fortunately, he failed.

One client suddenly stopped moving on a different trip up the Grand Teton with a party of four. Peter climbed down to see what was happening but couldn’t get any response from her. She was frozen in place – catatonic with fear. He told her over and over just to focus on her feet, and eventually, she snapped out of it and was able to resume the climb. She had no memory of the event. Years later, she returned to Exum with her daughter and attended climbing school. Peter always thought fondly of her, even though he hadn’t been sure what would happen if she could not continue.

Near the end of Peter’s tenure at Exum, he had another party of four on the Grand Teton. It was early in the morning, still dark. Peter knew the conditions would be favorable if he could see the airport beacon at the Idaho Falls, ID airport from a place early on the route called the Watering Hole. But if he couldn’t see it, weather was likely coming in. Guiding the Grand Teton is always tricky because storms typically approach from the southwest, which means often the clouds can’t be seen until they’re directly overhead.

By the time the group reached the start of the technical portion of the climb it had started to snow lightly. Since Peter had been unable to see the beacon and recognized the signs of an impending storm, he turned his party around. One of the clients was furious: “Shrieking at me! Not screaming, but shrieking! He was so upset that I wasn’t going to take him to the top of the mountain.” They returned to the hut at the Lower Saddle, and after a little bit, Peter noticed that the client was nowhere to be seen. Another client said the man had been so angry that he’d descended alone. Luckily, the client safely maneuvered the 40-foot headwall cliff and made it back to the valley. He then promptly complained to the park about Peter. The park, however, didn’t take the client’s gripes seriously. They understood enough about climbing to know Peter had made a wise choice.

It was clients like that one, though, that made guiding less and less appealing to Peter. When he started as a guide, it was the golden age of climbing. The clients were fit, capable and eager to be contributing team members. They didn’t mind the responsibility of belaying other people in their group, even if they’d never met those people prior to arriving at the climbing school.

Unlike Peter’s shrieking Grand Teton client, they didn’t feel that by virtue of paying their money, they were entitled to get hauled up to the summit. As time went on, Peter encountered more clients who felt entitled, weren’t fit enough and didn’t have the proper mindset to successfully climb the Grand Teton on a guided trip. He thinks this was a reflection of society as a whole – instead of taking responsibility, too many people were focused solely on getting what they could for themselves.

Not Cut Out to Be a Private Guide

Peter realized early on that he did not have the temperament to become an excellent private guide. He preferred guiding groups because, after the trip, he was done. More time was required when guiding private clients – phone calls and meetings before the climb to discuss gear, dinner afterward – and as much as Peter enjoyed a free meal, he would rather have his time to himself when not out in the field.

Peter did have many clients whose company he genuinely enjoyed, and these were exceptions to his rule. He guided a farmer from one of the Dakotas for several years in the Tetons. The farmer’s cousin had perished in the Everest tragedy of 1996, so Peter got to hear a lot about what had happened. Earlier in his career, he guided former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara multiple times and was impressed with the man’s sense of integrity and purpose.

He became good friends with another client, Larry Zaroff, a cardiothoracic surgeon and noted teacher. After conquering peaks in the Tetons, they did a first ascent of Chulu West, a high-altitude peak that turned out to be 21,600 feet tall, not 20,000 feet as previously thought. The steep rock headwall below the summit ridge was quite technical and required several pitches of protection with pitons. Once on the ridge, they had to make sure they didn’t stray to the north into China/Tibet, even though the terrain looked quite inviting.

A mentor of Peter’s once said, “Guiding must look like friendship even though it isn’t.” Peter realized that he was constitutionally incapable of pretending to be friends with someone if that wasn’t the case. He admired guides who had the personality to be friendly to a wide variety of characters, which was a skill he did not possess. Nevertheless, he carved out a niche for himself as a solid group guide, and it served him well throughout his guiding career.

To be continued…if you missed “Part 1: From Benchwarmer to Mountain Guide” you can read it by clicking here.

Sign up for the Exum History Project Mailing List (if you’re not already) to be notified when the next part of Peter’s profile is ready – click this link

This profile is based on phone, in-person, and email conversations with the author and Peter Lev between February 2015 and May 2022; letters Peter wrote home to his family in the 1960s; Peter’s short self-published autobiography from 2012, “The Next Pitch;” interviews in the Grand Teton National Park archives; scrapbooks kept by Beth Lev, his mother, containing newspaper articles of his expeditions; and various articles and books noted in the footnotes.

For more on the “Night of the One-Eyed Devil” rescue of the Appalachian Mountain Club members, former climbing ranger Pete Sinclair’s book We Aspired: The Last Innocent Americans is a great read and also goes into the accident in depth (thanks to Gary Gettman for the suggestion)

FOOTNOTES:

[1] “Chapter X: The Grand Teton,” in The Governor’s Wife: A View From Within, by Jessie F. Sargent, Marlborough House, 1973 and email communication with Dave Dornan, August 22, 2022. [Return to story]

[2] This was Buford Brauninger’s second close call in the Tetons. While being guided on the North Face of the Grand Teton in 1960 by Eddie Exum and Barry Corbet, he narrowly missed being crushed by a rock. See Eddie Exum’s profile for the story (https://exumhistory.com/thwarted-by-apple-pie). [Return to story]

[3] “The Night of the One-Eyed Devils,” Part II, Sports Illustrated, by James Lipscomb, June 20, 1965. [Return to story]

All rights reserved. To contact the author:

Great to read this history. A reminder that “tribal knowledge” is indispensable in the world of mountain guiding.

Thanks, Mike! I completely agree with the importance of that “tribal knowledge.” A critical piece. Kim