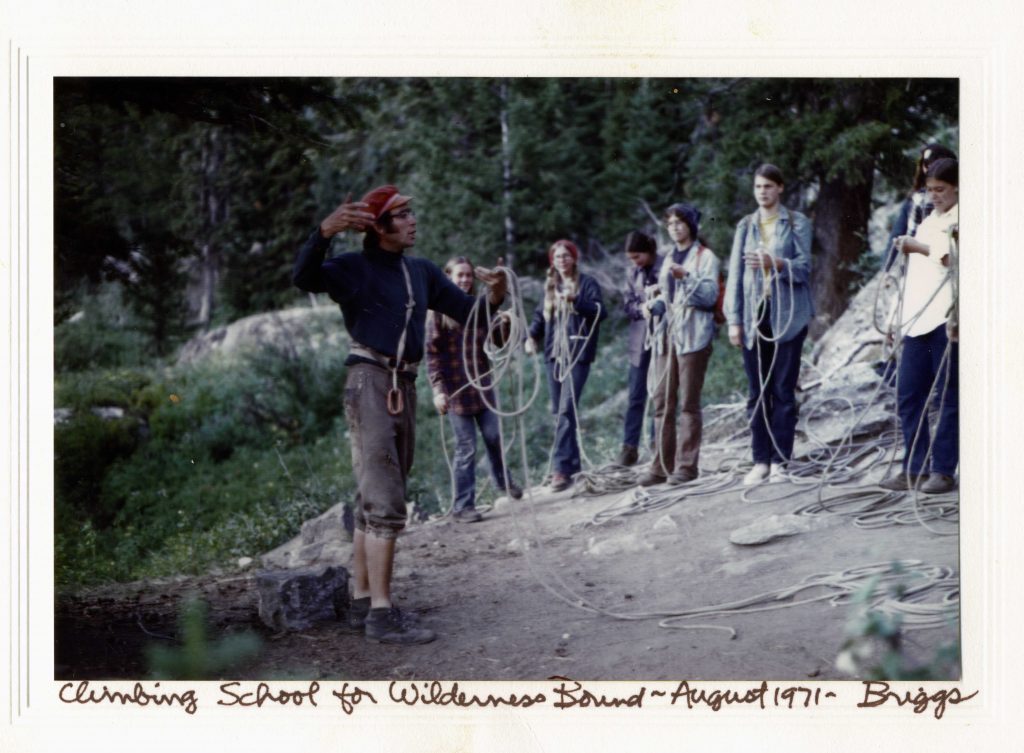

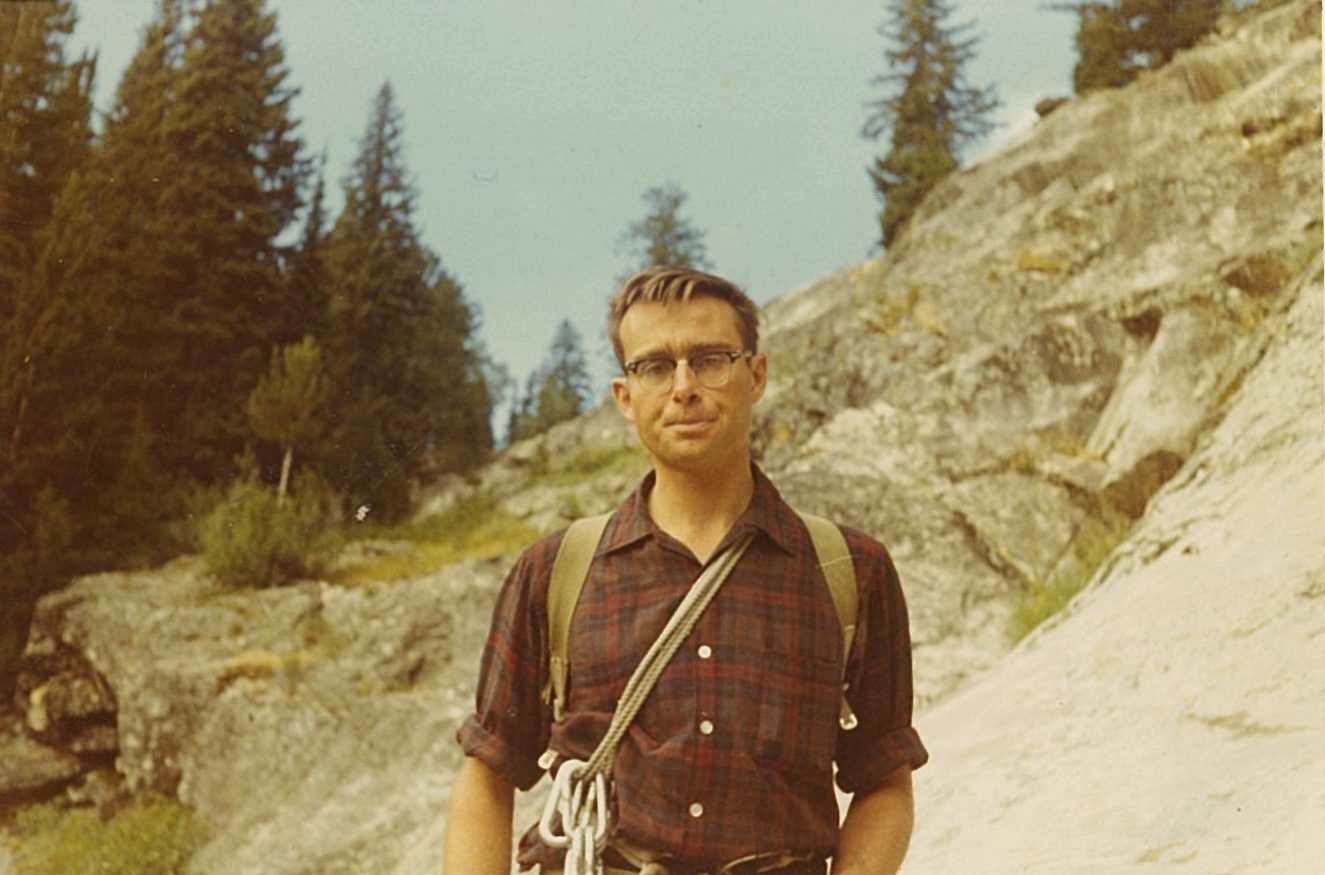

A Profile of Bill Briggs, Exum Guide from the late 1950s to early 1980s

One of the most striking things about Bill Briggs is how often he laughs – it’s infectious, gleeful. It sums up his approach to life: always looking for the positive. This is all the more remarkable because he’s had plenty of reasons to be pessimistic, starting with the fact that he was born without a hip joint, underwent surgery at two years old to carve out a socket, and ultimately had it fused in 1961. It was frozen in place and never quite worked properly after the fusion, but Briggs didn’t allow it to keep him from doing what he wanted. He has achieved athletic feats that most people with all joints functioning at 100% could never have accomplished.

His early upbringing in Maine helped prepare him for the life he would ultimately lead. His older sister was a physical education instructor/trainer, and she had him swimming, canoeing, and tumbling regularly. His sister took him skiing once, and then he borrowed his father’s skis to practice on hills near their home, despite the skis’ excessive length. Every winter, his family sawed chunks of ice out of a frozen lake and hauled them up to the family’s summer camp to put in storage. The lake was far enough away to require an overnight, and Briggs remembers huddling together with his brother to stay warm in bitter winter conditions. He claims he never thought much about these experiences, not realizing until later how much they taught him about survival in the woods and that what he assumed was a normal childhood was far from it.

Inspiration at Exeter

His family valued education and sent him to prep school at Philips Exeter Academy. Although he had not previously been allowed to participate in school sports due to his hip, Exeter required him to participate along with everyone else, and he flourished. He joined cross-country and the squash team and spent several Sundays on the ski slopes. Not only did he improve as a skier, but this cemented what would become a lifelong love of music. He and fellow skiers entertained themselves by lustily singing ski songs on the train rides back from North Conway. The camaraderie it created convinced him that anything of value required music.

His English teacher, Bob Bates, had been on K2 and started a Mountaineering Club. Briggs found Bates to be a “very inspirational character” and decided that if mountaineering were Bates’ sport, he would take it up, too. Briggs wanted to do anything he could to be more like Bates.

He remembers a winter adventure with the club climbing up Mt. Lafayette to spend the night at a cabin. The temperature was well below zero, it was getting dark, and one group member struggling with hypothermia had slowed down considerably. Briggs helped carry that person’s backpack, then pushed through the snow and broke trail up to the cabin, allowing everyone to reach the safety of the hut. This was when he discovered that not only did he find this sort of activity to be a great adventure, but it was something he was cut out to do, despite the challenges. Briggs recalled to biographer Lou Dawson, “It was a fabulous experience yet brutal – my mouth froze open … even with the hardship I was looking around at how beautiful everything was; the stunted bushes coated with rime, snow formations; and the moon hanging above scudding clouds.”[1]

After graduating from Exeter, he enrolled at Dartmouth in 1950 and discovered the Outing Club, the umbrella organization for all outdoor activities and an essential part of Dartmouth’s social life. Briggs thought the club was “really super, just wonderful…[I was] absolutely charmed by the whole thing.” He got involved with the skiing and mountaineering branches of the club, where he continued to push his limits. The mountaineering program had been founded in 1936 by Jack Durrance – the first in a long string of Dartmouth climbers to become guides in the Tetons.

Briggs ultimately ended up running the program when the focus of the other leaders turned to alpine skiing over climbing. He wasn’t the most robust climber due to his hip issues, but he made up for it with ingenuity and finesse. Briggs recalls Barry Corbet and Jake Breitenbach signing up for his course and wondering what he could possibly have to show these two excellent and seasoned climbers. After all, he had no reputation to match theirs – he simply liked climbing.

One day Corbet and Breitenbach were trying to get up an overhang and said to Briggs, “Why don’t you try it?” So Briggs took a sling (a loop of webbing), hung it on a knob, and used it as an artificial aid to get over. They were impressed, and Briggs was relieved that he had done well in “maintaining his stature.”

Discouraged by Dartmouth

This relationship with Corbet, Breitenbach, and the other climbers in the program would last even after Briggs left Dartmouth – well, let’s be honest – after he got kicked out of Dartmouth. He maintains he was just trying to create class spirit, but sometimes those attempts got out of hand. He remembers a tug-of-war between classes where he addressed his classmates, saying they should really get into it and not just play around. And they did. It turned into hand-to-hand combat and a game of King of the Hill. Briggs’ glasses got broken, and TIME Magazine purportedly described the event as a riot. In addition, he and his friends were climbing buildings and partaking in other “frowned-upon shenanigans.” Briggs believes the last straw was when he slalomed around the trees by the tennis court with his car. According to his great-niece, who lives in Hanover, “They’re still talking about you, Uncle Bill!”

His dismissal from Dartmouth led to a suicidal depression – not acted upon because Briggs “didn’t have the courage.” But with time, Briggs realized that leaving Dartmouth was not the significant loss he had first feared. While there were many things about the college he liked, there were more he didn’t. The educational experience paled for him compared to Exeter, which emphasized learning how to think. Far too frequently, he felt his Dartmouth professors were trying to tell him what to think. He recalled a professor asking everyone in a philosophy class if they believed in free will and being the only one to raise his hand. And he didn’t like the way that his roommates were treated, as “the only Jewish boy and the only Negro boy.” They were not allowed to join fraternities and were excluded from college life in other overt and subtle ways. He decided to stop trying to become a doctor and “somehow make a living by skiing, mountaineering and … music-making,” to his parents’ dismay.

Becoming a Ski Mountaineer

After his expulsion from Dartmouth, he stayed in Hanover, running the rock climbing program with Charlie Furrer, son of the Swiss guide Otto Furrer. He figured this would provide valuable experience on the path to becoming a guide himself. In 1955 he achieved his ski instructor certification and taught at Franconia in New Hampshire and for a brief while in Aspen, Colorado. Eventually, he moved to Vermont and started a ski school at the Suicide Six ski hill outside Woodstock. He hadn’t forgotten his friends from the Dartmouth Outing Club and invited them up for skiing lessons. Corbet had an epiphany when Briggs got him to parallel ski, which inspired Corbet to drop out of Dartmouth and teach at the ski school on a full-time basis.

Eventually, fellow Dartmouth students and climbers Sterling Neale, Bob French, Rick Medrick and Will Bassett also started teaching for him in Vermont. While Briggs developed his educational philosophy, Corbet pushed the edges. Corbet was a genius when it came to skiing as far as Briggs was concerned, capable of figuring out how to tackle almost any challenge. Briggs recalls that “we got so we could ski anything!”

Confident in his abilities and eager to showcase to North America how helpful skis were in mountaineering, Briggs dreamed up a 100-mile traverse of the Bugaboos to Rogers Pass in Canada. The expedition would require skiing, mountaineering, and climbing skills and the ability to navigate through terrain using unreliable maps, if any existed at all. Together with Corbet, Neale, and French, all expert skiers and mountaineers, the foursome set out on this 10-day trek in 1958.

Briggs recalls that he could lead most of it, but then they would get to a situation where he would think, “God, what do we do now?” Repeatedly, Corbet would step up, push through the impasse by dint of his sheer physical strength, and then step back and let Briggs lead again. Briggs can’t imagine a “better companion than Barry was for mountaineering…he was superb.” Ultimately, the friends completed the first high ski traverse in the Canadian Rocky Mountains, which Briggs says became a recommended part of the qualification standards for a ski guide in Canada.

Becoming a Guide at Exum

Briggs had done some climbing in the Tetons during his Dartmouth days, running into Exum guides Bob Merriam and Willi Unsoeld on the trail, who told him and his climbing partner that they should consider becoming guides for Exum. This interaction was in 1952, but Briggs wouldn’t begin guiding at Exum for another six years. Briggs’ ski school instructors and mountaineering club buddies became guides first: Corbet and Breitenbach, and by the late 1950s, French, Neale, Medrick, Bassett and Briggs had all joined the Exum crew.

In 1958, Briggs came back to the Tetons to explore the range more fully. He did a lot of climbing with Gary Hemming, a wiry young climber from California. Glenn Exum needed one more guide that summer, and Corbet introduced both Gary and Briggs to Glenn.[2] Briggs felt that Gary was much stronger physically, and would be a better fit, so he recalls letting Gary take the job. Later that season, Glenn needed another guide for the Grand Teton at the last minute. Briggs joined the trip, and that officially launched his career as a climbing guide.

Briggs found working at Exum to be everything he had wanted from his college experience but hadn’t received. He was surrounded by people he respected highly, all outstanding educators. There was Dick Pownall, who was masterful at handling people. Willi Unsoeld, the harmonica-playing religious philosopher who would push his clients well past their limits – and they loved him for it. Briggs’ good friend Barry Corbet always left things a little bit better than he found them. And Glenn Exum, a music teacher by trade, allowed his guides to develop themselves instead of telling them what to do. Glenn’s philosophy aligned with Briggs’ intuitive beliefs about education, and he considered it a privilege and an honor to work with Glenn and many of the other guides.

Pushing the Envelope

Briggs was particularly impressed by Unsoeld’s ability to successfully “push the adventure a little further than you would have thought it should go.” Unsoeld was constantly “stepping outside of the envelope” but getting away with it. No matter how outrageous, even Glenn said that Unsoeld’s clients always had the most incredible experiences. Briggs was passionate about ensuring that his clients also had outstanding experiences, so he would channel Unsoeld as much as possible. He would set up scenarios for his classes to practice skills: for example, pretending that a storm was coming in and they had to get off the mountain as quickly as they could. Using systems he and Corbet had worked out, his clients would zip down the rappel lightning fast.

Ultimately, one of these “Willi shenanigans” would contribute to Briggs getting fired from Exum. In 1978, Glenn was diagnosed with prostate cancer and sold the business to four of his guides: Peter Lev, Rod Newcomb, Al Read, and Dean Moore. Glenn had accepted Briggs pushing the envelope because, like with Unsoeld, Briggs’ clients loved it – Briggs recalls Glenn saying that his clients came back with “stars in their eyes.”

After the new owners – formerly Briggs’ fellow guides – took over, they began instituting what Briggs saw as unnecessary rules in the name of increased safety. Paul Petzoldt, who had founded the climbing school, used to say, “Rules are for fools,” and Briggs agreed. Rules don’t produce safety, he believed – it has to come from the person him or herself. And how did he get a client to take on this responsibility? He had to grant them “beingness” and allow them to recognize their own capabilities. Willi, he felt, was a master at this – at breathing life and confidence into his charges. Simultaneously, Glenn did this for the guides. Briggs believed that Glenn, who spun fanciful tales of each guide’s exploits as he introduced them to their clients, hoped to instill in them the confidence to be better guides than ever before so that they, in turn, could pass this on to their clients.

From Briggs’ viewpoint, the new owners moved away from this sense of individual responsibility to a sense of imposed morals. You will obey whoever has the authority: the owners, if you were a guide; the guide, if you were a client. This didn’t sit well with Briggs. He was convinced that this had no place in mountaineering: instead, each situation had to be looked at individually, and you needed to use “your own wits.” So along with his penchant for doing things differently from the other guides and pushing the envelope a-la-Willi, he was already butting heads with the new owners.

The Tennessee Boys

Things came to a head in 1982. Briggs recalls having a group of six friends from Tennessee in Intermediate School. He practiced another of his drills – down-climbing as fast as possible in the face of an imaginary oncoming storm – something else that none of the other guides did, to his knowledge. It was late August, and the Grand, Wyoming’s second-highest peak and the mainstay of the climbing school’s offerings, hadn’t been successfully climbed in at least a week due to snow. The group of friends, however, were clamoring to go. Briggs explained the risks to his “Tennessee boys” and said he didn’t want to take their money, but they kept pushing him, asking, “Is there any way?”

Impressed by their persistence, he told them it might be possible to climb the Grand that night before another storm came in the following morning. But they would be down-climbing and rappelling in the dark, and they’d have to climb the Exum Ridge as the shorter Owen route would be all iced up. Were they sure they wanted to do that? Five of them were, so he told Margo Urjavec in the office that he was off to climb the Grand that evening. She said, “Go for it, Briggs!”

He made it clear to the group that they had to reach specific points by certain times, or they would have to turn back. They made quick progress up to the hut, passing guide Don Mossman on his way down. Mossman was skeptical about their chances for success but also said, “Go for it, Briggs!” Upon cresting the Lower Saddle and arriving at the hut, Briggs was surprised to see the door open, as he thought his group would be the only ones there that night. Instead, Lev – one of the new owners – and a private client were there, having retreated to the hut after an unsuccessful attempt.

As Briggs started laying out his ropes, Lev asked incredulously, “You’re going up?” Briggs said, “Yeah.” Lev replied, “No, you’re not!” Briggs explained that this was what he had arranged with his clients. Lev said they had to go up the shorter Owen-Spalding route if they were going up. Briggs replied that he had already told his clients that the only way with a possibility of success was the Exum Ridge. Because the ridge is south-facing, he argued, the snow melts faster. Lev countered that it is also more difficult to retreat from if caught in a storm. Lev continued to express his disagreement with Briggs’ choice to attempt the climb, finally declaring, “I’d rather you don’t do it, but I expect you will.”

And Briggs and his Tennessee boys did, thanks to the weather holding off. They summited while still daylight, quickly descended the slabs as they had practiced, and rappelled as it turned pitch black. As Briggs went to turn on his flashlight, the clouds parted. Putting the torch away, they descended to the hut in the moonlight. Lev was still awake, frustrated and concerned for their safety. Soon after, Briggs was fired, as he remembers it. But it was a “great last climb.”

Again, Briggs didn’t let this dismissal hold him back, nor spend time dwelling on it – at least, not looking back through the lens of time. He went off and got “other adventures going.” As he says, “It’s been a fun life.” He feels that regardless of who owned the guide service, it was inevitable that guiding would change the way it did, although he found this disappointing. And, in his particular view of the world, more dangerous.

A Personal Miracle

Briggs is a long-time Scientologist, having been introduced to it after his hip fusion surgery in 1961. That recovery had been slow, and once he started skiing again, he sprained his knee so severely that he could barely walk. A friend of a friend offered to do what Scientologists call “Touch Assist” – a combination of touch and visualization to relieve pain. The treatment worked so well that it felt like a miracle to Briggs, and he immersed himself in learning more about the controversial religion, which he still practices today.

Scientology is a very contentious belief system, but it has had an enormous influence on Briggs’ guiding and his philosophy of risk-taking. In particular, the concept of the Affinity-Reality-Communication (ARC) Triangle informs many of his decisions.[3] Briggs is of the opinion that when all three parts strongly exist between you and your clients: Affinity (a sense of liking), Reality (an understanding or agreement), and Communication (an interchange of ideas), then you can operate with a much narrower margin of safety than you could otherwise. He says he would never have taken the Tennessee boys up the Grand that stormy night without a high degree of trust and good ARC. Briggs believes that Willi was able to take his clients on such wild adventures because of a similar connection with them, although Unsoeld was not a Scientologist and wouldn’t have used the same terminology.

Briggs also believes that if you had good ARC, you didn’t need rules, nor were you required to play by them if they existed. That is how he operated at the guide service, to the rightful consternation of the new owners. Although he conceded that rules were necessary for guides who didn’t have good trust and communication with their clients.

His ability to establish this trust and communication is what he believes allowed him to do things others viewed as too risky. Briggs once agreed to take two clients up Symmetry Spire, a challenging day climb, when he knew a storm was coming in and they would likely be in the range of lightning. He told them, “I’m game to do this because I’m very sure we will be alright, but it’s going to be the scariest thing you’ve ever done in your life.”

Sure enough, the storm came in as they got above the crux pitch. He hustled them 20 feet over to a gully adjacent to the ridge. After anchoring them to a piton (a metal spike driven into a crack in the rock), they had time to don their rain gear. They didn’t have to wait long for the action to arrive. The lightning hit somewhere above them with a “Kaboom,” and the resulting shockwave slammed the clients against the rock. Briggs thought, “Perfect! That’s just what I thought would happen.” He believed they would be safe in the gully, and he wanted to give the clients a “Willi” experience. But the owners felt the risks far outweighed the potential benefits, and Briggs remembers getting called out for doing that climb.

Mountaineering Traditions and Innovations

He and the new owners did agree on one important point: they were not there to do things the way the European guides did – taking people up the mountain on a leash and doing everything for them. As Briggs puts it, a client is “earning his way all the way at Exum. Making his own thing.”

Briggs says that if he had become an owner, he wouldn’t have been so quick to modernize the equipment, although he says there’s nothing wrong with keeping up with the state-of-the-art. But Briggs is happily old-fashioned and says that if he had been in charge, he would “still to this day be having all the clients doing a body rappel.” A body rappel involves using the friction created by wrapping the rope through the legs, over the shoulder, and down the back to slow the descent. That, he declares, is the “foundational stuff” of mountaineering (although it’s quite uncomfortable!). He says he would even be doing standing belays, except that Corbet disapproved of them, so he stopped.

Despite his love for traditional techniques, Briggs could also be innovative. He recalls using slings to make figure 8-shaped harnesses for his advanced clients before that became common practice. He taught his clients how to prusik their way back up a rappel – wrapping a short section of rope around the rappel rope to act as a self-locking brake – in case they ever got into trouble. One client who learned this technique from Briggs reported that it had saved his life when the rappel rope got caught around his leg and turned him upside down.

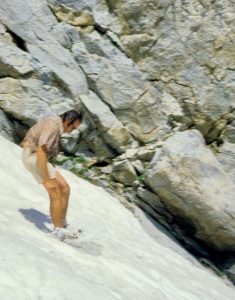

(photo courtesy of Berg Briggs, Bill’s son)

And Briggs was masterful at moving large groups of people through the mountains. He remembers having as many as 12 in a class and even once 12 on the Grand Teton. But the largest group he says he ever guided was a kids’ group of 31 on Cube Point. One assistant guide was with him, and he stationed the assistant at the top of the first pitch to belay. The one adult with the group remained at the bottom to entertain everyone while waiting their turn. Briggs ran two rope lines simultaneously, with the kids belaying each other on the less steep terrain while he kept everyone moving.

Afterward, the kids each wrote a stanza for a poem that they gave him to commemorate their climb. He’s lost the poem but says that now and then, one of those students will seek him out to reminisce about the impact that experience had on their lives. Usually, they track him down at the Hootenanny, where he can be found yodeling on a regular basis.

Yodeling and Teton Tea Parties

Briggs has long been known for his yodeling, which he learned with his Jewish-German roommate at Dartmouth. On Glenn’s 50th anniversary climb of the Grand Teton in 1981, Briggs was hiking up to join the others and started yodeling in his favorite place just below the headwall. Glenn heard it up at the hut, and when Briggs arrived, Glenn immediately asked him to yodel again. Despite being a bit out of breath, Briggs obliged, and this scene ended up in the documentary “One Last Song on His Mountain,” about Glenn’s climb.

Briggs also regularly yodeled at the Teton Tea Parties, which he created the summer he became an Exum guide in 1958. He would gather crowds of music lovers by a campfire to sing and play instruments, primarily climbers. The gatherings took their name from the Briggs family recipe of wine and tea with lemon and sugar that he served to his counter-culture guests. Biographer Lou Dawson said the parties became legendary, almost like a “mountaineering Woodstock.” Eventually, the parties got too rowdy for the park service, which put a stop to them.

Briggs went on to become a regular performer at the Stagecoach Bar in Wilson, WY and in 1993, convinced Dornan’s to let him resurrect the Teton Tea Parties in a tamer version known as the Hootenanny.[4] This weekly, open-mic gathering of musicians who perform for each other and curious tourists at Dornan’s Chuckwagon in Moose is going strong, with Briggs still at the helm.

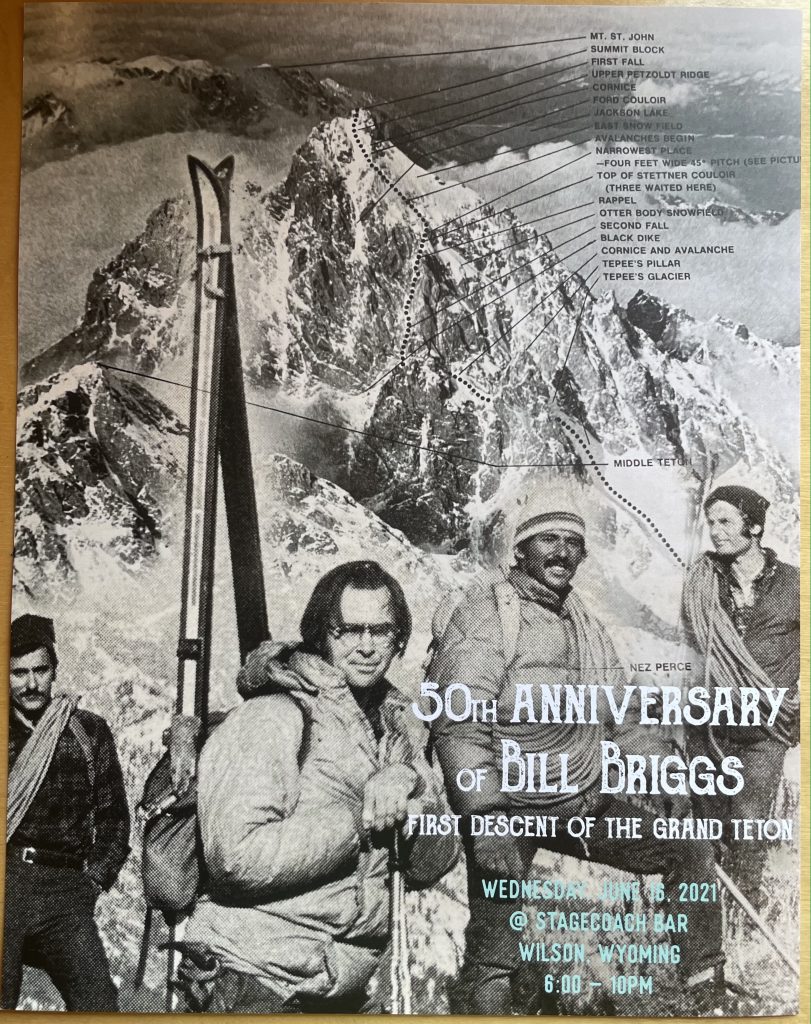

The First Ski Descent of the Grand Teton

But Briggs is perhaps best known for an athletic feat that cemented his place in skiing and mountaineering history – the first ski descent of the Grand Teton on June 15-16, 1971. Skiing the Grand Teton had previously seemed impossible, but Briggs proved it could be done. After having his hip fused in 1961, he slowly returned to skiing. Experimenting before the surgery with a splint he made to immobilize his hip, he knew he would still be able to climb and ski once he recovered.[5] In 1966, he became the ski school director at Snow King, Jackson’s local ski area, and began exploring extreme skiing in the range.

In 1968, he completed the first ski descent of Mount Moran’s Skillet Glacier. He tried to ski the Grand Teton on his own but was turned back due to poor weather conditions. The effort made it clear that skiing it alone would be too challenging, so when he attempted it again, it was with a support crew. Reminiscing about the improbably successful descent of mid-June 1971 with Powder Magazine 40 years later, he says that “the logistics, the timing… getting those right (is the important part). Whether you actually do the ski mountaineering is secondary. The big mistake is not being prepared.”[6]

Briggs had learned from his previous attempt and prepared relentlessly, running through scenarios for every possible situation. There was never a question in his mind about whether or not he could ski down it. The iconic photograph of his tracks – proof that he had actually done what he claimed – “symbolized the beginnings of U.S. ski mountaineering,”[7] according to Renny Jackson, former climbing ranger and author of the definitive guide to the Tetons.

Thanks to his pioneering high mountain traverse in the Bugaboos in 1958, his dedication to ski instruction, and his ski descents of Mt Rainer, the Middle Teton, Mount Moran, the Grand Teton, and Mount Owen, Briggs was inducted into the Intermountain Ski Hall of Fame in 2003 and the U.S. National Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame in 2008.[8] He’s also a member of the Dartmouth “Wearers of the Green” Athletic Hall of Fame, and the Ski and Snowboard Halls of Fame for the State of Maine, Jackson Hole, and Intermountain Instructors.

Still Skiing…and More

Briggs’ climbing days are over now, but he still gets out on the ski hill – in March 2021, at the age of 89, he was teaching clinics to a few select instructors at Snow King. That marked his 65th year of ski instruction, with the vast majority of it at Snow King, where he began teaching in 1965. These days he only has a couple of runs in him, and his fused hip causes a noticeable hitch in his walking gait, but he’s as graceful and fluid as ever on skis.[9]

And you can still find him doing what he loves just as much as skiing and climbing, if not more – playing banjo and autoharp, and of course yodeling, at the Stagecoach Bar in Wilson, WY. He helped found the Stagecoach Band and has played at the bar every Sunday night, with the exception of the COVID-19 pandemic, for 52 years – unless Christmas fell on a Sunday and the bar was closed. These days the band takes a break during the off-season, but in summer and winter, Bill – now 90 and forever a showman – continues to entertain the loyal crowd.

Sign up here to be notified when new profiles are ready!

This profile is based on in-person and email conversations with the author and Bill Briggs between July 2017 and October 2022, and the sources listed in the footnotes, especially Lou Dawson’s 2014 biography of Bill Briggs for Wild Snow.

All rights reserved. To contact the author:

Kimberly Geil, PhD

Footnotes:

[1] https://retro-skiing.com/2018/03/bill-briggs/ and “Beyond the Grand – Bill Briggs Biography” by Lou Dawson, July 3, 2014, https://www.wildsnow.com/13602/bill-briggs-biography-teton-ski/ [Return to story]

[2] To avoid confusion, Glenn Exum will be referred to as “Glenn,” as the name “Exum” is synonymous with the climbing school. [Return to story]

[3] From https://www.scientology.org/what-is-scientology/basic-principles-of-scientology/the-arc-triangle.html [Return to story]

[4] From “First Man to Ski the Grand Teton Celebrates 47th Anniversary of Descent,” June 15, 2018, by Ryan Dorgan for Powder: The Ski Magazine. https://www.powder.com/photo-galleries/bill-briggs-celebrates-47th-anniversary-of-grand-teton-first-descent/ [Return to story]

[5] From “Beyond the Grand – Bill Briggs Biography,” July 3, 2014, by Lou Dawson for Wild Snow. https://www.wildsnow.com/13602/bill-briggs-biography-teton-ski/ [Return to story]

[6] From “40th Anniversary: Bill Briggs’ Ski Descent of the Grand Teton: The man who skied the Grand reflects on the feat, 40 years later,” June 17, 2011, by Griffin Post for Powder: The Ski Magazine. [Return to story]

[7] From “Mountain Profile – The Grand Teton,” Alpinist 33, Winter 2010-2011, by Renny Jackson, p. 57. [Return to story]

[8] From the U.S. Ski & Snowboard Hall of Fame, “Bill Briggs – Hall of Fame Class of 2008.” https://skihall.com/hall-of-famers/bill-briggs/ [Return to story]

[9] From “Briggs reflects on 65 years of teaching skiing,” March 24, 2021, by Ryan Dorgan for the Jackson Hole News & Guide. [Return to story]

Dear Memories of Bill Briggs,

I climbed 12 summits in the Tetons in the 50’s including the

North Face of the Grand after an evening with Paul Petzoldt.

I will always remember the presence of Bill Briggs including

his ski descent of the Grand, and with him in the Canadian

Rockies and his guitar!

Thanks for the memories!

Virgil Day

Hi Virgil – that’s impressive that you climbed the North Face! I know that you did a lot with your brother. I’m glad you enjoyed Briggs’ profile and I look forward to sharing more of them!

Excellent article, Kim.

I was told that guides began using “Briggs’ Slab” as an initial test to see if clients could manage the Friction Pitch on the Exum Route. The slab is located at the base of the Owen-Spalding Route just below and north of “The Eye of the Needle” tunnel.