A Profile of Peter Lev, Exum Guide and owner from the early 1960s to the mid-2000s

When Peter Lev stumbled across a climbing book in his father’s library, he had no idea it would change the trajectory of his life.

Growing up in Southern California at the height of the Cold War, Peter never felt like he fit in. He hated physical activity of any kind and would much rather have been making model airplanes or drawing race cars. He was a quintessential nerd, so when his parents signed him up for the football team, he made sure he never left the bench. While he was interested in girls, dating was a foreign activity for him. And he had no desire to put his “shoulder to the wheel and fight evil Russians,” which is what he believed was expected of him.

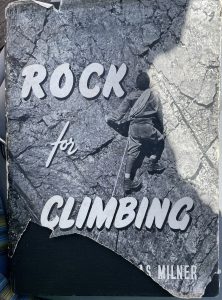

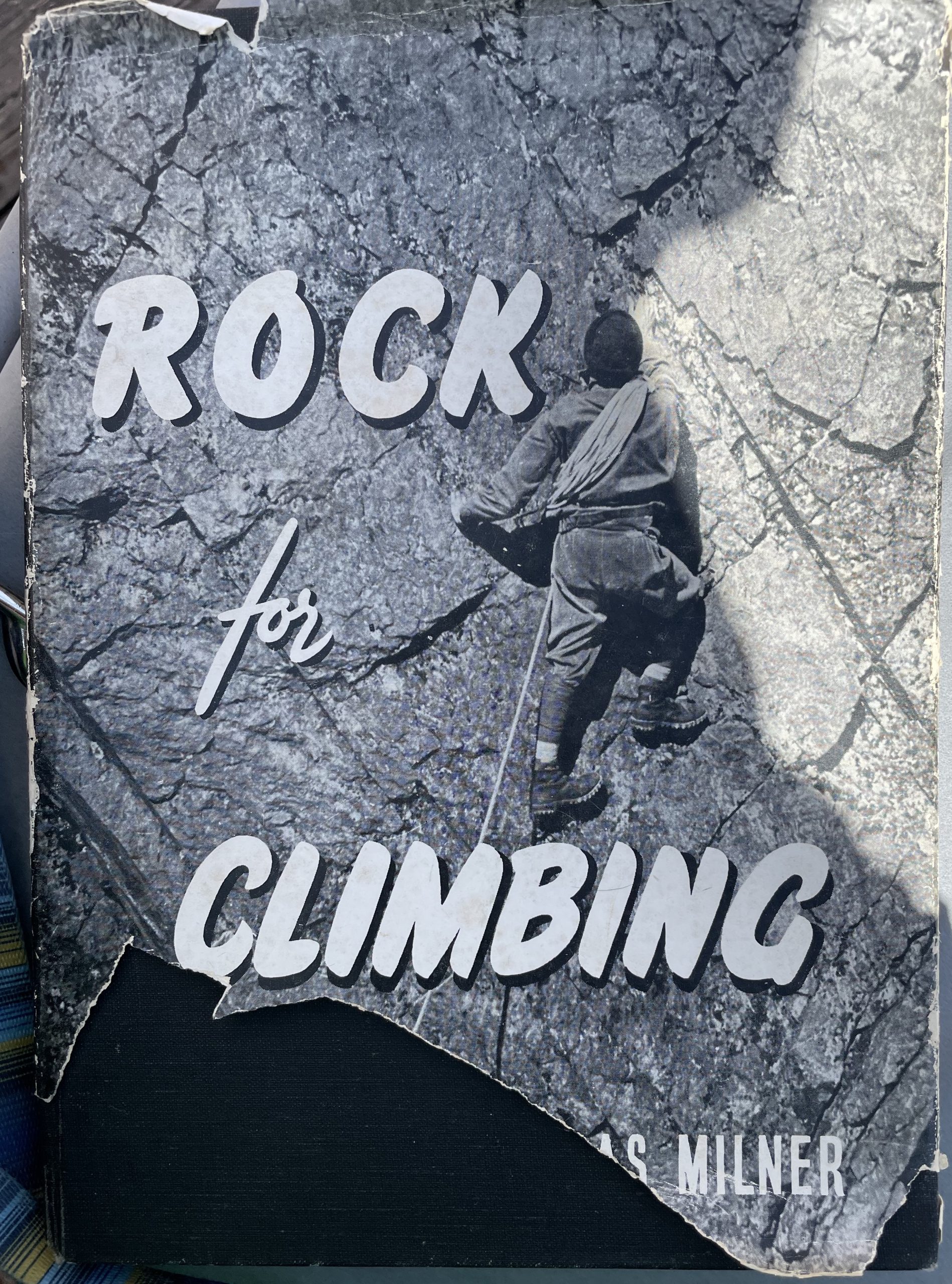

His parents were eager to find him a useful career, and his drawing ability provided evidence that he would make a good engineer. Not having any better ideas, he accepted that judgment. Until he found the book. It was a British book, called Rock for Climbing.[1] It changed everything.

The book’s stories of mountaineering in Europe captured Peter’s imagination. It was an escape from the suburban existence he found deadly boring, and it represented, as he put it, “a chance for a completely different life which I wanted desperately.” Rock for Climbing opened his eyes to a fabulous world, one that he became determined to explore.

He and his best friend from high school, Dave Reynolds, spent hours poring over the book together. At first, they were oblivious to the fact that people were climbing in the United States; they thought climbing was something that only existed in Europe. So they set out to reinvent it themselves. They started by hiking off trail in the Mt. Baldy area, which they could see from their homes on clear days.

Peter’s father had introduced Peter and his sister to the sport of skiing and eventually took them to Mammoth, a new ski area in the Eastern Sierras on the border of Yosemite National Park. From the top of the ski runs, the imposing skyline of the Minarets was visible. It looked just like the pictures of the Alps in Rock for Climbing. In other words, like mountains that real climbers would climb. With a trip to Europe highly unlikely, Peter and Dave hatched a plan to scale the tallest Minaret of them all: Clyde Minaret.

Climbing the Clyde Minaret

Peter was now 16 and convinced his parents to let him borrow the family car for the drive down. They had a Goldline braided rope that Dave had purchased, a few old iron pitons, and their Boy Scout tent and backpacks. Clothing was standard issue for the day: white t-shirts, Levi jeans and Levi jackets. Dave had received a little bit of climbing instruction, which didn’t count for much since neither of them really knew what they were doing. However, they had good common sense and were careful.

The climb was a low 5th class climb, not particularly difficult by today’s standards, but still considered a serious undertaking. It took them all day to get up the route, and they didn’t reach the 12,264-foot summit until sunset. They knew enough not to go back down in the dark, so they sat on top all night, hugging each other to stay warm. Peter remembers emptying out the meager contents of his backpack so he could put it over his head and breathe warm, recycled air.

When morning finally arrived, they shook feeling back into their hands and feet and began the descent, which required body rappels. They ran the rope between their legs, across the chest, over one shoulder, and down the back to create friction, and gripped it tightly with one hand to control their speed. Not the most comfortable method of descent, but standard practice before harnesses and rappel devices.

Moving slowly, they got caught in an afternoon thunderstorm. A flash of lightning hit, and the next thing Peter knew he was flat on his face, on a ledge only 4 to 5 feet wide. Had he been knocked off, that could have been the end of his story. But he wasn’t. After collecting himself, he and Dave waited out the storm, huddling together in the downpour. When they finally got back to their tent, the light was fading and they were completely soaked. But all Peter could think was, “That was great!”

Looking back on it now, Peter realizes that was the moment when it became clear that “something was obviously wrong” with him.

An Engineering Interlude

After that epic adventure on the Clyde Minaret, Peter’s father found him a summer job as a draftsman at an aircraft plant. Sitting at his desk surrounded by other draftsmen, he was filled with a sense of dread when he imagined it as his future career. Not only that, but the Cold War was in full swing. The Soviets had just launched Sputnik, and his fellow draftsmen were gleefully united in their hatred of the Russians. For reasons he couldn’t articulate at the time, he wanted no part of it. He had had a taste of freedom in the mountains, and he yearned to escape to the new and wonderful planet of climbing. One day he just couldn’t take it anymore. He marched up to the supervisor, told him he was quitting and walked out.

Despite the disappointing end to his drafting prospects, Peter’s father did quietly encourage his love of the mountains. Somehow, he knew it would be a good thing for Peter. Peter was allowed to choose where he wanted to go to college, and the driving factor for him was to be near mountains. He enrolled in the School of Engineering at the University of Colorado at Boulder (CU), trying to strike a balance between his family’s expectations and what he wanted for himself. He barely made it through the first year of engineering classes, but he did find a home in the mountains.

Learning from the Best

There were only a handful of hardcore climbers in town – a far cry from the hundreds or even thousands of climbers in Boulder today. When Peter arrived on campus, he was eager to connect with them. But how? The Rocky Mountain Rescue group, founded in 1947, proved to be the answer. He reached out to the organization and was introduced to Stan Shepard and other climbers. Stan, known for several first ascents in Eldorado Canyon, took Peter under his wing. Through climbs on the Flatirons – the notable formations towering over Boulder – and elsewhere, Stan gave Peter a good, safe foundation in climbing skills and techniques.

By his sophomore year at CU, he had met Dave Dornan, a talented climber who had grown up in Moose, WY, just outside of Grand Teton National Park. Dave studied philosophy and had a thoughtful way of approaching climbing, always being sure to do things right, no matter how long it took. Dave was also a visionary and was the inspiration behind many of the new routes being put up in Eldorado Canyon at the time. One of these was the first ascent of Yellow Spur, destined to become an Eldorado classic, with the soon-to-become legendary Layton Kor in 1959.

The crew that Peter climbed with included Dornan and Kor. Soon after Peter met him, Layton contracted valley fever on a trip to Yosemite in 1960, a potentially deadly disease affecting the lungs. Layton’s family sent him to a natural healing center in the Southwest for a cure, and Peter drove his very sick friend to the train station. When Peter picked him up a couple of months later, he was shocked at Layton’s appearance.

Already tall, Layton was toothpick thin after juice fasting for 45 days. Peter could see all his bones, but his eyes were large and glowing and he was clearly otherwise healthy. Layton wanted to go climbing, so they drove directly to Eldorado Canyon. Peter doesn’t remember what route they climbed, just that it was difficult and Layton floated up it. It was the beginning of Layton’s transformation into a world-class climber. Peter was content to be one of his belayers and soak up knowledge as Layton put up new route after new route.

In the early 1960s, Peter also climbed with George Hurley, who became another mentor to him. George and his friend Prince Willmon (yes, his name was Prince) liked to emulate the Europeans. George and Prince were fond of wearing wool knickers and wool dress coats when climbing, and Prince would even wear a tie. But Peter learned early on that climbing is not a game when Prince attempted Longs Peak in April of 1960. Caught in a significant storm, Prince and another climbing friend, David Jones, perished. Jane Bendixen, although badly frostbitten, was the only one of the trio who survived.[2]

The Grand Tetons

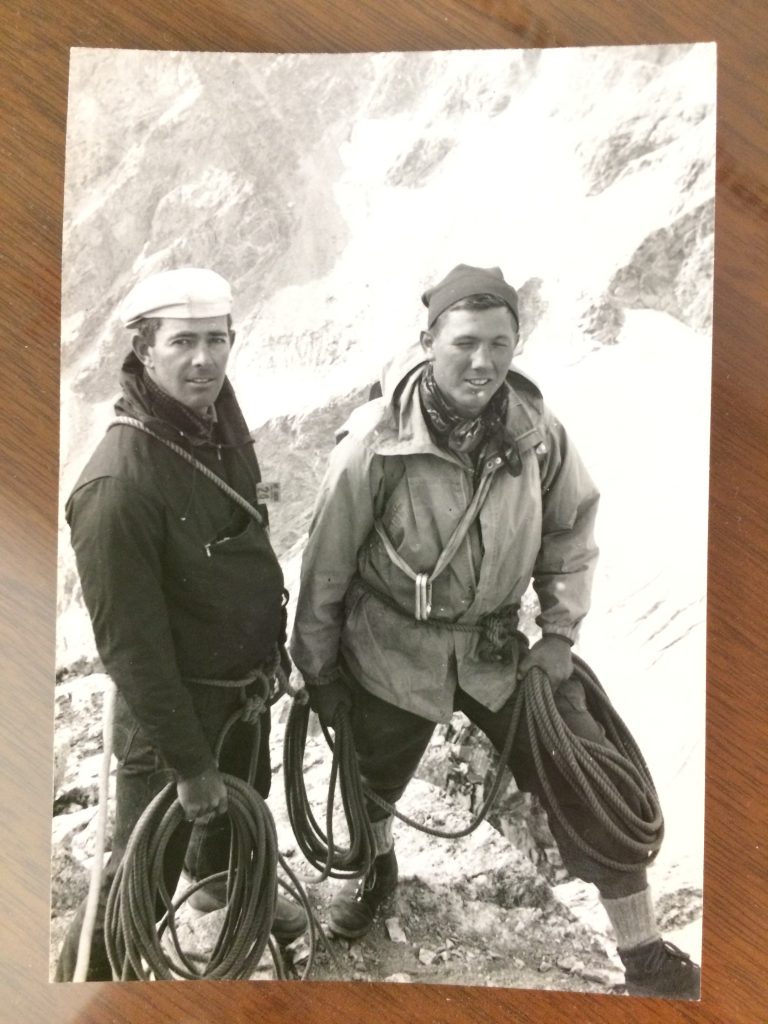

It was Dave Dornan who introduced Peter to the Grand Tetons. He invited Peter to join him in the summer of 1960. They hitchhiked to Wyoming, looking quite a sight with their mountaineering gear: huge packs, ropes, and puffy down jackets to protect against the cold. In some small towns they found themselves in, the locals would slow down and drive past them three or four times just to get a good look. Usually, they got rides reasonably quickly, but once, they shivered for nearly nine hours before someone took pity on them.

Upon finally arriving in Moose, WY, they spent their first night with the Dornan family, who owned the only private restaurant and bar in the park.[3] Dave then moved into park housing, a perk of his position as a climbing ranger that summer, and he helped Peter find a spot in the climber’s camp on the south side of Jenny Lake. They spent the next three days exploring so that Peter could see what climbing in the Tetons was like. He wrote to his family, “These Tetons are big mountains, surely bigger than anything in Colorado (as far as the amount of actual climbing you have to do). They look just like the Alps!” He had discovered an entire range of mountains that exceeded his childhood fantasies.

He met all the guides, who he thought were more “normal” than the climbers he knew from Boulder. One of them was also a student at CU and had been president of one of the fraternities when Peter was going through rush the previous year. Peter didn’t know it at the time, but this fraternity boy and climber would ultimately have an outsized impact on the course of Peter’s life. Fraternity life, however, did not appeal to Peter, and he eschewed it in favor of the local climbing scene.

Adventures as a Bellboy

Peter needed a job in the Tetons and found one working as a bellboy at the Jenny Lake Lodge. He was paid $80/month, plus room and board, and for the most part, enjoyed working there. He didn’t make as much as he could have at the larger Jackson Lake Lodge, where bellboys earned an average of $12/day in tips, compared to his $5/day. But since he worked the late shift, he made up for this by helping himself to food from the unlocked kitchen after the manager had departed for the day. In a letter home, he told his parents that he would surely get fat if not for all the climbing he was doing.

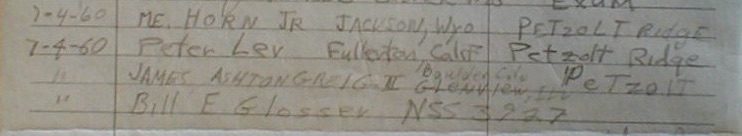

The climbing would ultimately mean the end of the job. Peter climbed as often as possible, leaving as soon as his shift was over or early the following morning. One time, he started a new route on the South Buttress of Mount Moran with Dave Dornan. He spent his 4th of July climbing the Grand Teton via the Petzoldt Ridge, thrilled with “the exposure becoming greater with every lead” and the steep snow requiring the use of crampons. By mid-July, Peter had decided that the Grand Teton was “easily the finest mountain that I have ever been on.”

Rarely did these climbs allow him to get back to work by 3 pm when his shift started. He arranged with the other bellboy to cover for him until he returned, usually around 6 pm, and then he would work extra the following day. That worked out fine until he set out to do a route on the Underhill Ridge of the Grand Teton on July 12, 1960 – the first time he had personally conceived of and organized a first ascent – along with Jim Greig, William Glosser, and David Laing.

The climb was a success, but it began to snow while they were rappelling. Given the difficulty of the terrain, they decided to stay put and spent 3.5 hours hanging in stirrups beneath an overhang, waiting for the storm to pass. It wasn’t overly cold, and Peter actually found it rather fun. But he got back way later than the other bellboy could stay, and the manager at the Jenny Lake Lodge really “blew his stack.” He demanded to know whether Peter was there to work or play and upon hearing Peter’s response, gave him an ultimatum. In the heat of the moment, Peter quit.

The following day, he wondered if he had done the right thing by resigning. But what was done was done, and he was thrilled to finally be free to pursue climbing, as that was ultimately his goal for the summer – to improve his ability and gain experience.

Losing the bellboy job at Jenny Lake Lodge also crystallized what climbing meant, as he continued to explain himself and his decision to his frustrated parents. He had asked the manager several times if it would be possible to arrange his schedule to have two days off in a row but was always told, “No.” And while he recognized that he had lost a fine job at a good location, even if it didn’t pay that well, he argued that climbing meant a great deal more to him than just “going overboard on a hobby,” as his parents suggested. Climbing, he wrote back, “…is not entirely useless. I think it is doing me a lot of good. You learn judgment, you learn to know yourself, other people, and many other things which I couldn’t begin to explain.”

Freed from his bellboy responsibilities, Peter started to climb regularly with the former fraternity president from CU-Boulder, Al Read, including a first ascent on the West Arete of No Escape Buttress in Leigh Canyon. Al was as enthusiastic about the mountains as Peter. They became friends and climbing partners, which led to the opportunity that would define Peter’s life for decades to come.

A Shift in Fortunes

Through Al, who had started guiding at Exum the summer before, Peter began to consider guiding as something he might be able to do himself. Before coming to the Tetons, he had previously thought it only took place in Europe. By August of 1960, the mountain climbing school was short on instructors. Al recommended Peter to Glenn Exum, the school’s charismatic owner.

Peter was still staying in the climbers’ camp. He and his friend Jim Grieg had found a wrecked tent cabin, covered it with black plastic to keep the rain out, and claimed it as their spot. Most of the climbers were a sight to see – unkempt and living on the fringes of society. Peter was the only one with short hair, decently clean clothes, and who had actually had a bath in recent history. Those characteristics, along with Al’s recommendation, are in his mind why he passed muster with Glenn and his wife, Beth.

To this day, he is incredibly grateful to Glenn for choosing him. He didn’t pick guiding, and guiding didn’t pick him – Glenn did. Not only did Glenn give him his start in what was to become his lifelong profession, but Glenn also gave him multiple second chances along the way.

When he got hired, he went on a couple of trips up the Grand Teton with Glenn to make sure he had the necessary skills to become a guide. When Peter came to Exum, he lacked social self-confidence, but he was young, determined, and strong. After getting Glenn’s stamp of approval, he learned by working with more experienced guides. Peter was all ears, listening to everything they said and watching their every move. It never occurred to him to question the senior guides. He had enough brains to know that they knew so much more than he did, and he wanted to learn it. There were particulars to get right everywhere – at the school practice rocks, on the mountain – hundreds of tiny details with potentially enormous consequences.

Peter doesn’t know where else, as a 20-year-old, he would have had the opportunity to be entrusted with people’s safety and, literally, their lives. But he understood it was a huge honor and was dedicated to doing his absolute best. He knew the risks – they had no radios or cell phones, and there would be no easy way of getting help if anything went wrong. He was committed to doing everything right.

As he got his first taste of guiding that summer and then became a full member of the team the following summer, other things began to change for him. He and Al had become good friends, and after finishing for the day, they would head over to the Jackson Lake Lodge.

To his amazement, Peter found that his high school status as a nerd had been completely transformed. He and Al were now the “football players,” and boy was it fun! They would sit at the counter in the restaurant, and their favorite waitresses would serve them a full dinner and only charge them for a cup of coffee. They’d take showers in the girls’ dorm since there weren’t any at the guide camp. They would often spend the night in the girls’ dorms, too, which they weren’t supposed to be doing. Peter was having the time of his life.

To be continued…

Sign up for the Exum History Project Mailing List (if you’re not already) to be notified when the next part of Peter’s profile is ready – click this link

This profile is based on phone, in-person, and email conversations with the author and Peter Lev between February 2015 and May 2022; letters Peter wrote home to his family in the 1960s; Peter’s short self-published autobiography from 2012, “The Next Pitch;” interviews in the Grand Teton National Park archives; scrapbooks kept by Beth Lev, his mother, containing newspaper articles of his expeditions; and various articles and books noted in the footnotes.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Rock for Climbing, by C. Douglas Milner, Chapman & Hall Ltd: London, 1930. [Return to story]

[2] See http://publications.americanalpineclub.org/articles/13196102302/Colorado-Longs-Peak for more details on this tragedy. [Return to story]

[3] It is still family-owned to this day, and the Spur Bar has one of the best views to be found of the Teton range. [Return to story]

All rights reserved. To contact the author:

The Peter Lev I never knew!!!

Wow! The story of Pete Lev becoming a mountaineer and mountain guide is fascinating! It depicts the most unlikely youth who became such a notable climber, with huge influence from the likes of Dave Dornan, Layton Kor, Al Read, and of course my dad, Glenn. It was a pleasure and privilege to know and work with such fine and talented gentlemen as the Exum guides.