A Profile of Peter Lev, Exum Guide & Owner from the 1960s to 2000s

This is the third part of a profile about Peter Lev, former guide and owner of Exum Mountain Guides in Grand Teton National Park. Part 1 covered his early years and how he got interested in climbing, and how he initially became a guide at Exum. Part 2 shared adventures he had guiding unusual clients and assisting with rescues in the park. This section covers a major climb he and several friends did in 1963 – a new route on Denali – and his time in the Marines.

In 1962, the first American expedition to climb Mt. Everest was in the works. A full quarter of the party were Exum guides: Jake Breitenbach, Barry Corbet, Dave Dingman, Dick Pownall, and Willi Unsoeld. Peter looked up to them, especially guides like Barry and Jake, who were only a few years his senior. Inspired by the upcoming Everest expedition, Peter and several of his climbing buddies acted on a dream of their own: attempting a new route on Mt. McKinley (now known as Denali, or “tall one,” as the indigenous Athabaskan people have always referred to it).

Denali is the highest peak in North America, topping out at 20,310 feet. Since the base of the mountain is at 2,000 feet, it is actually a longer distance to the summit than Everest, which rises from 14,000 feet to 29,028 feet.[1] In 1963, several unclimbed features promised adventure and challenge for those brave enough to try[2], and the scrappy young climbers were eager to test themselves on a high-altitude expedition.

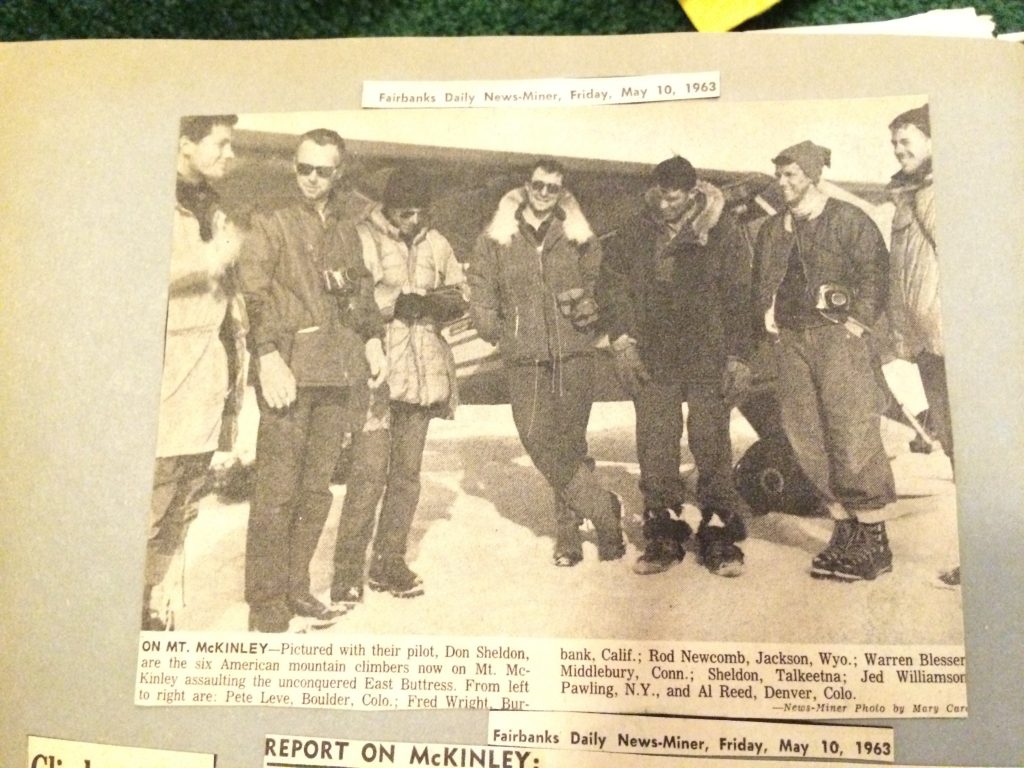

The nucleus of the group were climbers who knew each other from Boulder and the Tetons: Peter, Al Read, Rod Newcomb, and Jim Grieg. Peter and Jim had climbed with Warren Bleser a few times in Boulder and invited him to join. Warren had experience on Denali, having attempted it in 1961. His party had been turned back by an avalanche that swept away all their gear, so Warren was keen to try again. Warren recruited Jed Williamson, a climber from the East Coast who had been to Alaska, and Fred Wright, another Teton guide, eventually rounded out the crew.

Peter was still studying at the University of Colorado at Boulder, but he took a leave of absence during the 1963 spring semester to prepare for and participate in the trip. He and Jim oversaw buying and packaging all of the food supplies and many other expedition details. Peter was also focused on getting into excellent mountaineering shape. His parents wanted him to come back to California. He explained he needed to stay in Boulder both to help Jim with the preparation and to take advantage of being able to shadow the Arapahoe Basin Ski Patrol. He wouldn’t get paid, but it would allow him to spend time at altitude and improve his skiing. When not in the mountains, he lifted weights, ran, or cross-country skied whenever there was enough snow.

By mid-February, the complications of managing an expedition overwhelmed him. He wrote, “Expedition work has been taking up a lot of time. Nearly all correspondence is directed here and has to be answered. Grieg is at present not around, so I have had to do it all. Problems with leadership and route, money for Al to buy specialized stoves in Europe, delays in our boot orders, and worst of all food…Food logistics seem impossible.” Despite the challenges, the group eventually wrangled all the required supplies.

Peter’s friend and fellow Exum guide Fred Wright joined the expedition in April, which boosted his spirits. As he wrote to his family, “Fred has given up quite a lot to come and he is very enthusiastic. I am very pleased that he is coming.”

Jed Williamson had a connection with Bradford Washburn, the famed adventurer and cartographer, and the team consulted with him as part of their preparation. In 1960, Washburn had created a map of Denali using aerial photographs he had taken in the 1930s and the knowledge he had gained from his successful climbs of the peak.[3] They pored over the pictures he shared with them, looking for the best route. Washburn suggested climbing the East Buttress, and they agreed. While getting to the base of the East Buttress was straightforward, the crux of this new route would be reaching the top of it, as it featured technical terrain including two nearly vertical ice cliffs.

By April, all the supplies and gear were secured, and the departure date was close by. In a stroke of bad luck, Jim Grieg broke his leg skiing just before the trip and could not go. Peter was sad about leaving his good friend behind, but too excited about what lay ahead to mope around for long.

Heading to Alaska

For the Teton climbers, getting themselves and their gear to Alaska was quite an endeavor. Rod had a Dodge he had bought for about $75, and they purchased a trailer to pull behind it for about $150. The car couldn’t make it up Teton Pass outside of Jackson, WY, on its own, so their friend Frank Ewing towed them up to the top. Ewing had driven to Alaska before and assured them it would be all downhill from there. After five days of hard driving, the crew arrived in Fairbanks, grateful to have avoided any significant breakdowns in the middle of the desolate Alaskan highway.

Upon reaching Fairbanks, they sold the car and trailer and met up with the other two members of the expedition: Warren Bleser and Jed Williamson. In a letter Peter wrote home on April 17, 1963, he said, “We Teton climbers had been working together a long time, and Warren and Jed seemed like a rude intrusion at first. Now, however, that we have spent 3 days organizing the gear, I feel much better. We are coming down to the line and the closer I get, the better I feel. We are well organized and all set.”

Peter was eager for his first glimpse of McKinley, writing on the train to Talkeetna, “We will arrive about 4:30 in the morning. And then, when it becomes light, we’ll have our first look at the biggest mountain in the world (McKinley is the biggest mountain in mass and greatest height from base to summit). They say it is so big from Talkeetna that it blots out the sky. And by the time the day is over some of us may be on the Ruth Glacier. What a transition!” Don Sheldon, the legendary bush pilot, would fly the team and all their supplies up to the Ruth Glacier, where they would begin their ascent of the mountain. Peter closed his letter by saying, “Gad! I can hardly wait until tomorrow morning!”

The next day, April 18, he added a postscript: “We are here. The mountain is big and looks like a cloud. Warren just flew in with Sheldon and the rest of us will soon follow.” Bleser had appointed himself as the de facto trip leader due to his previous experience on the mountain and was flown in first. The rest of the group had decided that all decisions would be made democratically, and there was no need for a leader – but Peter recalls that Warren insisted on claiming the leadership mantle, which rankled him. The rest of them had drawn straws to determine the order in which the climbers and their 1500 pounds of gear and supplies would be flown up to the 6,000-foot mark on the glacier.

Peter had drawn the short straw, and it was too dark to fly by the time it was his turn. He spent the night on the floor of Sheldon’s dwelling, surrounded by scattered junk. Despite Sheldon seeming to be a “strange, backcountry man,” Peter appreciated the excellent (and he hoped, free) meal that Sheldon provided. By 9:00am the following day, they were in the air. Flying a mere 100 feet above the Ruth Glacier, Peter saw the remains of three dead moose on the ground below, killed by a bear. Denali, he wrote to his parents, was “incomprehensibly towering above all.” Spruce boughs tossed out of the plane provided enough contrast against the white for Sheldon to gauge where to land on the vast expanse of the Ruth Glacier. As the plane touched down on a little ice shelf, the tents and the rest of the team were a welcome sight.

On the Ruth Glacier

Conditions were challenging on the mountain that May. It had rained up to 15,000 feet, leaving places where there was nothing but sheets of blue ice. Brad Washburn said, “She’ll be tough climbing this year.” Washburn had only seen such a phenomenon once before, 10 years earlier. Rain at such altitudes is rare.

First, they needed to reach the base of the East Buttress. The climbing wasn’t difficult, but crevasse conditions had made it unsafe for Sheldon to drop the team and their gear as high up the Ruth Glacier as planned. The weather prevented him from returning to fly their supplies up, and they had to shlep their gear an additional eight miles. Over the next ten days, when they weren’t pinned down by storms, they established a camp at the halfway point that they called Alpsport Camp, and ultimately a Base Camp near the top of the Ruth Glacier.

By April 30, after each man had made several heavy carries from Alpsport Camp, all the gear was at Base Camp. Now the real climbing could begin. Al and Warren had reached the bottom of the East Buttress that first day. On May 1, Peter, Jed, Rod and Fred set off to push the route higher. Peter wrote in his journal that he got the “difficult lead” on a section they came to call “The Bulge.” He described it as “very steep, rotten ice overlaid by rotten snow then a foot thick snow slab. I am uncertain and very slow. I take most of the morning for these 150 feet. At the top, fix lines and bring load up.” Climbing a big mountain like Denali involves constant hauling of gear to establish camps, each one higher than the next. Planning to be there for up to six weeks, there was no way they could carry all the gear at once, so they would climb up, establish a route and a camp, and then go back down for more equipment. This was an exhausting process, but one that also had its merits; they would be in excellent shape and well accustomed to the altitude by the time they would make their summit push. The effort involved in carrying everything the extra distance up the glacier hadn’t hurt, either.

Near Misses

May 2 dawned bright and clear, but they ended up having two very close calls. While Peter and Jed ascended the Bulge, ankle-deep in soft snow, a slab broke loose. Avalanche! The snow swept over them, but they were anchored to the lines they had fixed to the slope, and the lines held, to their relief. Later in the day, a massive slab broke loose, tumbling tons of ice and snow straight toward Base Camp, where Fred had remained behind. The team held their breath as the cloud settled, wondering if they had lost all their gear, as happened to Warren’s first expedition in 1961, and their teammate. But luck was on their side. The blocks stopped just short of engulfing the camp. They thought Base Camp was in a relatively safe location, but they had been mistaken.

After a frightening night, at which they “jumped at the slightest noise,” according to Peter’s journal, they moved Base Camp to a knoll just below the East Buttress, well out of any avalanche paths. The sun was hot and bright and required them to take two trips carrying gear, which Peter recorded as the: “heaviest loads I have ever carried.” But their new site for what they called Advanced Base Camp was much better situated.

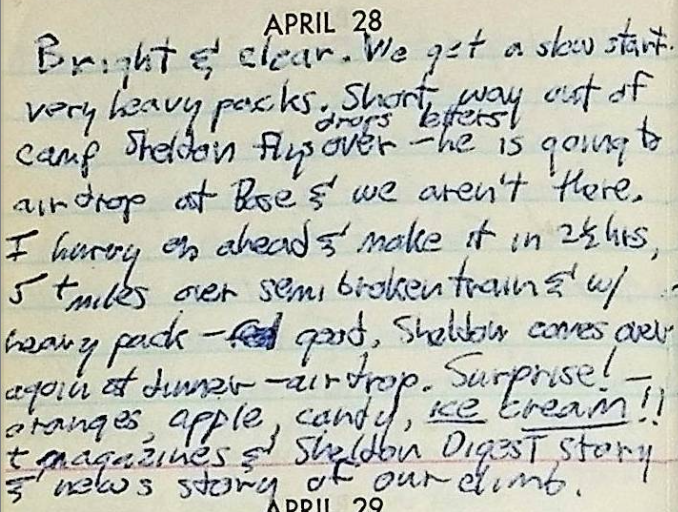

Over the next 16 days, the team slowly pushed the route higher and higher, establishing Camp I at 11,100 feet, Camp II at 12,400 feet on May 13, and Camp III at 13,700 feet on May 19, just below the top of the East Buttress. When the weather allowed, Sheldon would fly over to drop mail and supplies and report their progress to the outside world. The first time they received one of these drops, Peter wrote: “Surprise! Oranges, apples, candy, ice cream!! + magazines + news story of our climb.” After another of these fly-bys, Sheldon described the climbers as “hanging like spiders from the sides of the cliffs.”

As they forged their new route on the East Buttress, they dodged avalanches while threading their way up ice ramps, gullies, and cliffs. Storms swept through several times, making climbing impossible and forcing them to hunker down in their tents. On some days, the wind chill made temperatures bitterly cold, but they kept pushing upwards. Peter wrote in his journal on May 8 that it was “the coldest I have almost ever been – my breathing hurts.” On other days, when there were no winds and the skies were clear, it was “unbearably hot.” Mother Nature is fickle on a big mountain, and she would be again.

East Buttress Surmounted

By May 20, over a month since the expedition had begun and 20 days since they started the technical portion of the route, the climbers reached the top of the East Buttress at 14,630 feet, the first climbers ever to do so.

Although they were still 6,000 feet from Denali’s summit, the most challenging section of the climb was behind them, and they were confident of reaching the summit. On May 22, they all attempted to reach Denali’s apex, but it was not to be. Fred contracted altitude sickness, and Peter and Al turned around to help him back to camp. Warren, Rod, and Jed continued up but blizzard conditions forced them to turn back below the summit. Fortunately, they had wanded the route on the way up (stuck 3-foot poles in the snow to mark their path), and the would-be summit party found their way back to camp in the storm.

They made it back just in time. An intense North Westerly storm pinned them down for two days at their high camp, at 17,450 ft on the Thayer Ridge. The wind was so strong there was nothing to do but lie in their tents and hope they didn’t get blown off the mountain. Cooking or heating water was a constant struggle. By the second day the snow was so heavy that the center pole in Peter’s tent started to collapse, and they had no choice but to take it apart. They lay there, cold and uncomfortable, while the tent fabric flapped in their faces. North Westerly storms can be deadly, but looking back, Peter remembers how much he loved the adventure.

Second Summit Attempt

When the weather let up, Peter, Al, and Rod decided they would have another go at it. Still dealing with altitude issues or exhausted from the previous attempt, Fred, Jed, and Warren stayed at the High Camp. Fortifying themselves with both dinner and breakfast before setting out, the trio climbed all night in the bitter cold, triumphantly reaching the summit of Denali, at 20,030 feet, on the morning of May 25, 1963. With the wind chill, the temperature was around 20 below, so they only had time for a “few freezing photos” on the top. Peter was pleased with how good he felt at that altitude. It was the highest any of them had ever been. With the wind hounding them, they retraced their steps back to High Camp.

After sleeping and eating, the whole crew packed up their gear and started the trek down. They still had cumbersome loads, so much so that the weight of Peter’s pack tipped him over on the first fixed line on the upper ice. The storm had also deposited vast amounts of snow, whipped into slabs by the wind, but they managed to avoid any further avalanches. Sheldon flew overhead and reported back to their families and the local correspondents that they had summited and were on their way down.

Ready for Pickup

By May 28, they had descended without further incident to the Ruth Glacier at approximately 8,000 feet, where Sheldon would pick them up and fly them back to Anchorage. Rod, Al, and Jed headed further down the glacier to the skis and sleds they had cached at their drop-off point over 40 days before. Warren, Fred, and Peter stayed at the higher camp. Fred was still recovering from altitude sickness, and Warren had gotten heat exhaustion on the way down. It’s hard to believe that they were shivering in their tents just a few days earlier in howling wind and blizzard conditions. As for Peter, he opted to stay with Warren and Fred due to a case of indigestion. The team had done their best to eat up their supplies rather than carry them, and Peter had made a particularly impressive effort at consumption. This was a decision he would come to regret.

Rod, Al, and Jed got flown out successfully, but then the weather soured yet again, stranding Warren, Fred and Peter on the glacier. It was ten long days before Sheldon could pick them up. By that point, they were running out of food. Peter had brought a copy of Michener’s Hawaii with him, and it came to the rescue. They tore pages out of the book, rolled tea leaves inside, and smoked them to pass the time and tamp down the hunger pangs.

After a few days, the weather improved enough for Sheldon to make a pass and drop them some food. Disappointingly, the airstrip they had tried to stamp out wasn’t packed down enough for him to land. But the extra supplies revitalized them enough to snowshoe back up to their advanced base camp and retrieve some non-perishables still on the mountain.

On June 6, Peter recorded that it was their “50th day in this icebox. If I am correct, only the old pioneers Belmore Brown and company[4] spent that long in here.” Peter didn’t sleep well that night. He had a feeling that tomorrow would be the day. June 7 dawned clear, and they were out working on the airstrip by 6am. A little before noon, Sheldon appeared with landing skis attached and finally touched down. After being stranded for 10 days on the glacier, the plane was a welcome sight.

Surprise Visitor

Sheldon told them that Peter had been officially ordered to be flown out last, and flew out Warren, followed by Fred. Sitting alone in the vast amphitheater of the Northwest Fork of the Ruth Glacier, Peter wondered what was up, and had an idea.

Sure enough, when Sheldon came back the third time to pick up Peter, he had a passenger. Peter’s father, Lester, was on board to greet his son. Peter embraced him with a smile, saying, “I thought it was you!”

Since there was only enough room in the plane for one passenger at a time, Lester stayed on the glacier after a brief reunion while Peter got flown back to Anchorage. By then, it was getting late in the day, and Peter was worried his dad might have to spend the night, but Sheldon made one last flight. After 51 days on the mountain, the entire team was back in civilization. Hot showers and fresh food were never so appreciated.

Peter had no time to relax, though. The storm that stranded him, Warren, and Fred on the glacier for ten days had made him over a week late to report for duty with the Marine Corps. In fact, Peter’s father was there in large part to make sure Peter fulfilled his military commitment. After one night in Anchorage, Peter was on a flight to Camp Pendleton.

Joining – and Leaving – the Marines

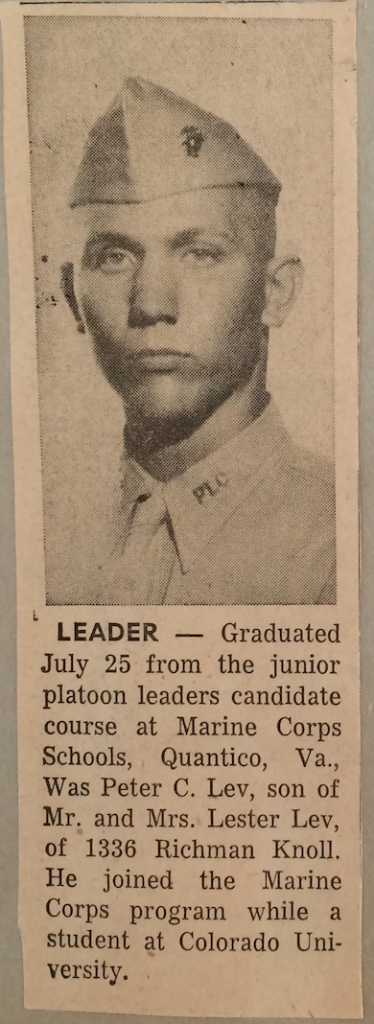

How did Peter end up in the Marine Corps when it was clearly a poor fit for his interests and temperament? When Peter started college, he searched for the most exciting thing to do. Having watched too many war movies, he signed up for the Reserve Officer Training Corps in the Marines. After one summer of training in Quantico, VA, he realized he’d made a colossal mistake. The six weeks of officer training made it crystal clear it wasn’t the right place for him, and he dropped out. This changed his status to that of a private.

He was supposed to report for summer training and monthly meetings, but when he switched his mailing address, it took time for the bureaucracy to catch up. Every six months, he changed his address between his parents’ house and where he currently lived. This allowed him to escape detection and focus on climbing. But of course, the Marines caught up with him, coinciding with the completion of the most incredible experience he’d ever had in his life.

The Denali climb opened a new world for Peter. He and his teammates were the only humans on their side of the mountain in April and May. “The snow was so white and clean and everything was just great.” He loved it. He had found his passion – mountaineering – just as the Marine Corps found him.

Camp Pendleton

When he arrived at Camp Pendleton, he was quite the sight. His face was ruddy and sunburned, except around his eyes where the glacier goggles had kept his skin snow white. He was assigned to a disciplinary company due to his shenanigans with the mail. Most of the other men in the unit could hardly read or write, and Peter had almost nothing in common with them. He found them “the worst of the worst, and the majority of them were mean-spirited and down-right despicable.”

Not only that, but he didn’t want to be there. He wished he could simply daydream about how amazing the Denali trip had been. He cleaned his rifle but paid someone else to shine his shoes, belt buckle, and the bill on his hat. He didn’t care how much it cost. He just didn’t want to do it.

The bullies honed in on him like heat-seeking missiles. He was not only literate but college educated. He’d just pulled off a successful Alaskan expedition and resembled a raccoon. All of this made him a natural target. The sergeant and lieutenant in his platoon had sympathy for him and protected him to some degree, but that only made the bullies madder.

The Fight

One afternoon, three of them cornered him, yelling that they were going to beat the living daylights out of him. They had his back up against a wall, but he wasn’t about to go down without a fight. He used the only weapon he had at hand and brought the butt of his rifle down on the first bully’s foot, hard enough to hear the bones crack. When that man crumpled in pain, he whipped up the gun and used it to hit the second thug in the face, and the third wisely ran away.

It was the closest he’d ever come to acting out some of his teenage war movie fantasies, but the reality was not what he had imagined. The rage he felt overwhelmed him such that he was grateful his rifle was not loaded.

Shortly after that incident, he was sent to see the camp psychiatrist. The psychiatrist didn’t say much but signed some paperwork and then had an orderly escort him out of the camp gates. Just like that, his military service was over. He suspects the platoon leaders pulled some strings to get him out of there, knowing it would be best if he were gone. He never heard from the Marines again. He knew not to ask – he was lucky he hadn’t been court-martialed.

To be continued…

Click here to read Part 1: From Benchwarmer to Mountain Guide

Click here to read Part 2: Accidents and Adventures in the Tetons

*************

This profile is based on phone, in-person, and email conversations between the author and Peter Lev between February 2015 and May 2023; letters Peter wrote home to his family in the 1960s; a journal Peter kept during his McKinley climb; Peter’s short self-published autobiography from 2012, “The Next Pitch;” interviews in the Grand Teton National Park archives; scrapbooks kept by Beth Lev, his mother, containing newspaper articles of his expeditions; and various articles and books noted in the footnotes.

*************

FOOTNOTES

[1] From the National Park Service, Denali National Park & Preserve, “The Alaska Range and Denali: Geology and Orogeny,” https://www.nps.gov/articles/denali.htm. [Return to story]

[2] Washburn, Bradford, “Mount McKinley – Proposed East Buttress Routes,” 1963, American Alpine Journal. http://publications.americanalpineclub.org/articles/12196345300/Mount-McKinley-Proposed-East-Buttress-Routes. [Return to story]

[3] “Bradford Washburn, Explorer, 96, Dies,” by Jeremy Pearce, Jan 16, 2007, for the New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/16/obituaries/16washburn.html [Return to story]

[4] Belmore Browne and Herschel Parker made three attempts to be the first to climb Denali. On their last go in 1912, they spent nearly five months approaching Denali from Seward, only to be turned back a few hundred feet from the summit by bad weather. From http://publications.americanalpineclub.org/articles/12195521600/Belmore-Browne-1880-1954 and https://www.rei.com/blog/climb/famous-u-s-summits-denali-alaska. [Return to story]

*************

All rights reserved.

Kimberly E. Geil

www.ExumHistory.com

Peter’s Denali climb story riveting— beautifully written

RIP Pete, it was great climbing and learning from you.