A Profile of Bob Merriam, Exum Guide in the 1950s.

Revised and updated Jan 31, 2022.

Bob Merriam did one of the earliest midnight climbs of the Grand Teton, and he almost didn’t live to share the story. For most of his working life, he was a well-respected professor of cellular biology, retiring as department chair from Stony Brook University in New York. But there was a time when he had a second calling – he was one of the three guides at Exum Mountain Guides in the 1950s.

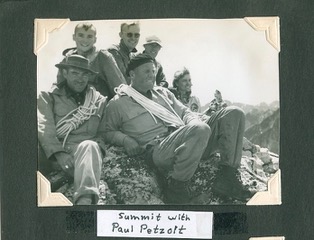

The Iowa Mountaineers and Paul Petzoldt

Merriam grew up in Iowa, far away from any big peaks. In college he joined the Iowa Mountaineers, and through their outings began to visit more mountainous places. On an expedition to the Sawtooth Mountains in Idaho in 1947, the group’s guide was none other than the legendary Paul Petzoldt.

Petzoldt was the original climbing guide in Grand Teton National Park and founder of what is now Exum Mountain Guides as well as the National Outdoors Leadership School (NOLS). Petzoldt was known for being quite a character. On this trip in the Sawtooths, the group encountered a glacial lake returning from a climb. While Merriam and his classmates walked around the lake to keep their boots dry, Petzoldt waded up to his waist in the ice cold water, just to show that he could do it the most direct way.

Petzoldt’s style was to involve people in the climbing, and Merriam, a natural climber and teacher, ended up helping out as an assistant on several of those climbs in the Sawtooths. They chalked up an astonishing 11 first ascents on the trip, including Warbonnet Peak – a worthy adventure even today[1].

In the summer of 1949, Merriam and a friend visited the Tetons to climb for a couple of weeks, where they briefly met Glenn Exum. Petzoldt had introduced Glenn[2] to climbing and guiding in the early 1930s, and they had become partners in the Petzoldt-Exum School of American Mountaineering. Twenty years later, Petzoldt was busy with other adventures, namely homesteading on a ranch he’d won in a government lottery near Riverton, WY[3]. Glenn was single handedly running the climbing school, now known as the Exum-Petzoldt School of American Mountaineering.

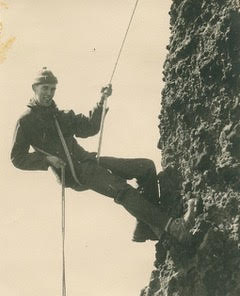

Becoming a Guide

In the spring of 1950, Merriam got a call from Glenn inviting him to become a guide. Merriam gladly accepted, believing that Petzoldt must have recommended him to Glenn, and he must have also made a favorable impression when he’d met Glenn the previous summer. Merriam loved climbing and the thought of being paid to climb “thrilled him to death.”

When Merriam began guiding in 1950, there were only two other official guides – Dick Pownall and Mike Brewer. Merriam, Pownall, and Brewer would each guide a few times a week. Glenn was running the guide service, and Glenn’s wife Beth took care of the office and kept the books. Merriam remembers Glenn as being a fabulous storyteller and musician, and a good horseshoe player who always treated the guides fairly. Beth was an equally marvelous person, and working for the couple was a pleasure. After each day’s climb, Glenn or Beth would pay the guides in cash – half of that day’s take. Merriam felt they were paid well, and he would go home with money jingling in his pocket at the end of the summer.

Glenn showed Merriam the ropes – what was covered in the classes, the routes and variations at the Hidden Falls practice area and on the Grand Teton, and how to manage clients and set the pace. Glenn taught him to be patient and thorough: to make sure all the knots were tied properly, the belays secure, and the ropes tight.

Pownall, who had been guiding with Glenn for a couple of years before Merriam arrived, became a mentor to Merriam. Pownall had also grown up in Iowa, and came to the Tetons as a high school student when his uncle Paul Franke, then the superintendent of Grand Teton National Park, secured a job for him on the trail crew[4]. Merriam remembers Pownall as reserved but affable, and a strong climber who was always generous in telling him what to expect on the various routes.

A Bear on the Lower Saddle and Other Critters

On their first Grand Teton trip early one summer, Merriam and Pownall saw someone poking around by the Exum cache up on the Lower Saddle. Who could have beaten them to camp? They were the first ones to climb the mountain that season, and they hadn’t seen any tracks. As they got closer, they realized it was a bear! When the climbers appeared on the scene, the bear spooked and took off down a snow chute to the left of the steep headwall. But even a bear can lose its footing, and it slipped and went tumbling head over heels in a “brown avalanche” all the way to the bottom of the Middle Teton Glacier. After coming to a stop, it got up – fortunately none the worse for wear – shook itself off, and continued on its way. They were glad they had interrupted it when they had, as it had already ripped their tent open and was in the process of tearing into the tarp that protected all the rest of the gear, including the sleeping bags.

Once Merriam saw a sage grouse on the upper glacier, well above its natural habitat. He thought that bird must have had a very adventurous spirit. Another time, the night was filled with thousands of locusts flying overhead, heading from Idaho to Wyoming. He doesn’t know where they were going or why they were at 11,700 feet, but it was a sight he never saw again.

Dinner on the Lower Saddle when Merriam was guiding consisted of everyone throwing a can of soup into a big pot. Occasionally an empty soup can wouldn’t get carried down and a marmot looking for a easy meal would get its head stuck in one. The guides would hear a clunking noise as the marmot stumbled around, banging into the rocks. Feeling responsible for the unlucky animal’s plight, they would catch the critter and release it from its metal helmet.

The Midnight Climb of the Grand

Merriam and two strong clients once took advantage of a beautiful, moonlight evening to do a night climb of the Grand – something no one had done before, to their knowledge[5]. Unfortunately, a storm came in with lightning just as Merriam had led the Open Book pitch on the Exum Ridge. The sound of thousands of buzzing bees assaulted their ears as he had them set their metal pitons to the side and stand on the rubber soles of their shoes. Then he watched – both entranced and horrified – as blue flames of St. Elmo’s Fire built up three times near his clients, but then thankfully discharged further up the mountain.

After the lightning passed, it began to snow “like the dickens.” Merriam down climbed back to his clients, and they carefully picked their way along the icy rocks to a small ledge. It wasn’t big enough to sit down, and only slightly protected from the wind and snow. They spent a miserable night standing on the ledge, huddled together as they waited for daylight. Although they were nearly frozen through by the time the sun came up, they “stomped their feet” and continued on up to the summit. By the time they had gotten back down to the guide shack at Jenny Lake, Merriam figured they had been on their feet for over 26 hours. He hoped his clients had had their fill of adventure. As for Merriam, that was the last time he ever attempted a midnight climb.

He had other close encounters with the elements. Once he was enjoying lunch on the top of Cloudveil Dome, on a beautiful day with just a few clouds in the sky. He wanted to look at some of the impossible-seeming climbs on the nearly vertical walls of the imposing south face. As soon as he poked his head over the edge of the cliff, his hair stood up on end. Surprised, he pulled his head back and his hair lay back down. Intrigued, he leaned over again and had the same result. There was an electrical charge located just over the face, and when he pulled back from it, the charge instantly dissipated. The scientist in him was fascinated to experience an electrical field so vividly.

Another time on the Grand Teton he had a more intimate encounter. He was guiding a woman and her teenaged daughter up the Grand. They had almost reached the top when the weather suddenly closed in, and they began to hear the telltale sounds of electricity in the air. He got them all off the Ridge and squatting down, and doesn’t remember anything else until he woke up, looking into the terrified eyes of the woman and her daughter. He’d been knocked out. He thinks he must have touched something that gave enough of a charge to render him unconscious, but fortunately not enough to cause further injury. The clients were scared to death, knowing that without their guide, they would be trapped on the mountain until help arrived. But that wasn’t necessary – the storm passed, Merriam quickly recovered, and they went on to finish the climb without incident.

The First Ascent of the Red Sentinel

Merriam recalls that on days off, he and the other guides would always go climbing – they just couldn’t get enough of it. Early in his first summer Merriam, Pownall, and Brewer were joined by their friend Leigh Ortenburger. Ortenburger wrote a widely-used guide book of the Teton range, now updated by Renny Jackson, a former climbing ranger and Exum guide. The foursome had their eye on an unclimbed pinnacle called the Red Sentinel, considered one of the last “big problems” in the range, according to Pownall.

At first, the climbing was straightforward – difficult, but climbable. That all changed at the last pitch, which was a 70-90 foot sheer cliff, around the corner from the belay stance, dropping precipitously to the Teepe Glacier down below. Pownall took the first stab at it but found it surprisingly delicate and slippery, with little to no protection. After messing around for a bit, Pownall thought “This ain’t for me.” Returning to the belay ledge, Merriam said he’d give it a go.

Merriam took over the lead, and slowly eased his way around the corner. He tried twice to get pitons in, but lost each one on the first whack of his hammer. Soon he reached a point where he realized if he continued up, he wouldn’t be able to climb back down. This was in the days before harnesses, so any fall would be painful if not fatal as the rope tightened around his body. But Merriam wasn’t thinking about failure. He was focused on the problem in front of him, and as he scrutinized the face, he saw small cracks that just might go. Gritting his teeth, he launched past the point of no return.

Pownall couldn’t believe that the rope kept feeding out, as he fully expected Merriam to have to retreat. Pownall and the others were beginning to worry that things were getting too serious when they finally heard a yodel from Merriam – he had made it past the crux and was standing on top. After Merriam brought his climbing partners up to join him, Pownall and Ortenburger agreed that it was “a pretty impressive lead for a married man.” Marital status aside, climbing historian Paul Horton calls Merriam’s effort on the Red Sentinel one of the “greatest, boldest leads in Teton history[6].”

Leaving Guiding

After seven summers of guiding, Merriam felt he had to let it go, even though he wanted to continue. This is a decision that Glenn likely approved of – Glenn felt strongly that mountain guiding was not a proper career for the intelligent, educated men he preferred to hire. As a school teacher himself, he wanted his “boys” to move on to a meaningful career and family life after their tenure in the mountains.

Merriam, then a rising professor with a young family (his son, Craig, was born in 1954, and his daughter, Donna, followed the next summer), was feeling the pressure to stay at the university in the summers. Guiding in the Tetons rather than doing research in the lab was affecting his career trajectory. As the demands continued to mount, he finally decided to leave guiding behind for the sake of his academic career and his family, after the summer of 1956. He became a professor of cellular biology, first at the University of Pennsylvania, and later at Stony Brook University on Long Island. He retired in 1990 as department chair.

He has no regrets, but leaving guiding was a tough decision. Guiding was a job he was well suited for, and he loved every aspect of it – the pay, the work, his boss, the people. Looking back, he considers those summers spent guiding in the Tetons as the best of his life. Climbing, he says:

…for people who have well coordinated bodies and a lot of energy and a love for the outdoors and are not too afraid of heights or can control it, it’s just a marvelous way to get outside. There is a goal, there are techniques, there is comradeship, there is the solving of problems, there is testing of yourself. … It’s just a marvelous way. I can’t think of a better way to form companionships and jointly trust your[selves] to the rope and each other.

Merriam never lost his love for the mountains, and came back several times to take each of his children to the top of the Grand Teton. When climbing wasn’t an option, they went camping and canoeing. These days, in his late 90s, he leaves the actual climbing to younger, stronger legs, like those of his grandson, Willie, who climbed the Grand Teton with Exum Mountain Guides in 2016. But his mind, sharp as ever, fondly recalls those golden years in the Tetons as an Exum guide.

******

This article is based on phone, in-person, and email conversations with the author and Bob Merriam between April 2016 and March 2019, phone conversations between the author, Bob Merriam and Dick Pownall in September 2016, and written memories of events by Bob Merriam and Donna Merriam Weems, and Dick Pownall.

******

All rights reserved. To contact the author:

Are you signed up for the Exum History Project Mailing List? If not, click this link!

Footnotes

[1] See https://iowamountaineers.tripod.com/leaders.htm, https://www.idahoaclimbingguide.com/bookupdates/warbonnett-peak-10200/, and the 1948 American Alpine Journal, p. 106 for more information on the Sawtooths expedition and the first ascent of Warbonnet Peak. Thanks to Paul Horton and Bill Fetterhoff for drawing my attention to these sources. [Return to story]

[2] To avoid confusion, Glenn Exum will be referred to as “Glenn,” as the name “Exum” is synonymous with the climbing school. [Return to story]

[3] Ringholz, Raye C. (1997). On Belay! The Life of Legendary Mountaineer Paul Petzoldt (p. 164). Seattle, WA: Mountaineers Books. [Return to story]

[4] Hornbein, Tom and Fred Wolfe. (n.d.) “In Memoriam: Richard Pownall, 1927-2016.” Retrieved from http://publications.americanalpineclub.org/articles/13201214088/Richard-Pownall-1927-2016 on Nov 30, 2017. Also based on comments made by the Rev. Carl Walker at Dick Pownall’s Memorial Service in Jackson Hole, WY, on June 29, 2017. [Return to story]

[5] As it turns out, it had been done, as early as September of 1933, when climbers noted in the Summit Register that they had summited at 8am after “3 hours moonlight climbing” http://www.tetonclimbinghistory.com/page19/files/1933_GT5_8-25-.jpg Another group, including Glenn Exum, claimed a “moonlight ascent – earliest in history” on July 1, 1934, reaching the summit at 4:30am. http://www.tetonclimbinghistory.com/page19/files/1934_GT2_6-25-.jpg Clearly both of these groups had better conditions than Merriam and his clients! [Return to story]

[6] Comment made by Paul Horton at Dick Pownall’s Memorial Service in Jackson Hole, WY, on June 29, 2017. [Return to story]

Nice article and pictures Kim!